"LA

SIEMPRE FIEL ISLA."

CUBA WITH PEN AND PENCIL

BY

SAMUEL

HAZARD.

"It

is the most beautiful land that eyes ever beheld."— COLUMBUS.

SOLD

ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION.

HARTFORD,

CONN.:

PUBLISHED BY THE

HARTFORD PUBLISHING COMPANY.

PITKIN AND PARKER,

CHICAGO, ILL.; MEEKS BROTHERS, NEW YORK; POWERS

AND WEEKS, CINCINNATI, 0HI0;

F. DEWING AND CO., SAN FRANCISCO

D. H. MCILVAIN AND CO., ST. LOUIS,

MO.

1871.

CHAPTER

XXXIX.

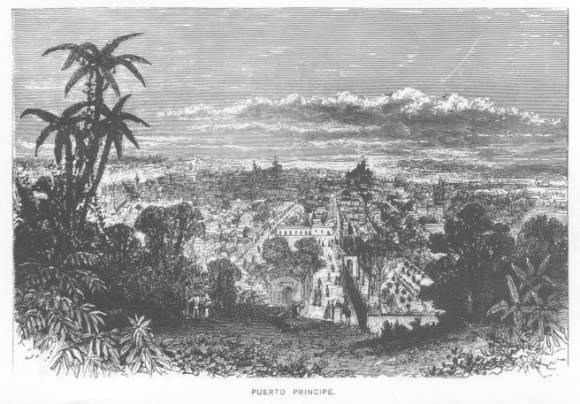

PUERTO PRINCIPE. Magnificence

of the bay—A superb May-day—Columbus at Nuevitas—Jardin del Rey—Port of

entry—Old Indian town—Camaguey —Sponge fisheries—Turtle fishing—Railroad to

Puerto Principe—Description of—Some reflections on Cuban hospitality—Lack

of hotel accommodations —Accepting invitations— The rebellion at Puerto

Principe— Potreros or cattle-pens—Original subdivision of land—Cattle

raising— Jerked-beef —The Cuban horse—Raising of—Wonderful gaits—Guava jelly,

how made—Handsome women— From Puerto Principe to Havana.

WHAT a glorious morning it is, as we come in sight

of this superb Bay of Nuevitas! — the very perfection of a May-day ; but such a

May-day as few northern eyes have ever seen, with the brightness of the verdure,

and the purity of the wondrous atmosphere and sky. And then the water,—it is so

hard to resist the temptation of its sparkling clearness and depth, and of its

seductively cool appearance, and not make a dash over-board. Irving, in

describing the feelings of Columbus on arriving off this very spot, says : " Columbus

was struck with its magnitude and the grandeur of its features ; its high and

airy mountains, which reminded him of those of Sicily ; its fertile valleys, and

long, sweeping plains, watered by noble rivers ; its stately forests, its bold promontories, and

stretching headlands, which melted away into the remotest distances." But we

have entered the bay, which gradually opens out into an immense land-locked

sheet of water. On its extreme southern side lies the small town of Nuevitas

itself, with its few white-walled houses glaring in the morning sun. The bay is

said to be the second one in size on the island, containing within its area

a space of fifty-seven square miles, though its depth is not very great.

this very spot, says : " Columbus

was struck with its magnitude and the grandeur of its features ; its high and

airy mountains, which reminded him of those of Sicily ; its fertile valleys, and

long, sweeping plains, watered by noble rivers ; its stately forests, its bold promontories, and

stretching headlands, which melted away into the remotest distances." But we

have entered the bay, which gradually opens out into an immense land-locked

sheet of water. On its extreme southern side lies the small town of Nuevitas

itself, with its few white-walled houses glaring in the morning sun. The bay is

said to be the second one in size on the island, containing within its area

a space of fifty-seven square miles, though its depth is not very great.

On

the 14th of November, 1492, Columbus anchored in this bay, to which he gave the

name of Puerto Principe, erecting a cross upon a neighboring height in token of

possession, and passing a number of days in exploring the collection of

beautiful islands in the vicinity, since known as " El Jardin del

Rey," or the King's Garden. This, it is said, was the foundation of

the town of Nuevitas,  which

was originally known as Santa Maria, but it was not until 1513 that a

permanent settlement was made under Diego Velasquez, when the principal

town was removed to the Indian village Caonao, and soon afterwards to the town

of Camaguey, now known by its name of Puerto Principe. Nuevitas, a town of about

six thousand inhabitants, gets its importance simply from the fact that it is

the port of entry for the city of Puerto Principe, situated in the interior, at

forty-five miles distance.

which

was originally known as Santa Maria, but it was not until 1513 that a

permanent settlement was made under Diego Velasquez, when the principal

town was removed to the Indian village Caonao, and soon afterwards to the town

of Camaguey, now known by its name of Puerto Principe. Nuevitas, a town of about

six thousand inhabitants, gets its importance simply from the fact that it is

the port of entry for the city of Puerto Principe, situated in the interior, at

forty-five miles distance.

As

a modern town, it made its commencement in 1819, under the name of San Fernando

de Nuevitas. It is a growing little place, and is becoming the depot of

shipment of a good deal of the sugar and molasses of the neighborhood, as well

as of large quantities of hides. As the war in its vicinity has been long

continued, and the port has some times been separated from Puerto Principe by

the patriots, it may now have grown into greater importance as the point of

supplies for that district in which the Spanish army

operates.

There

is also an interesting branch of commerce pursued here, though not amounting to

a very large trade. This is the sponge and turtle-fishing, carried on by almost

an entirely distinct set of people from those ashore. The sponges are those

mostly used on the island, and a rough

calculation estimates the annual production at one hundred thousand dozen, worth

one dollar per dozen, which is quite a business for a people who carry it on as

they do. The turtle-shell is prepared usually for export, the meat being sent to

the markets of the vicinity in which the turtles are caught. It is quite an amusing sight to see the

habitations of these people, dotting some portions of the bay; and as

it-is almost perpetual summer, their life is not a very

unpleasant one. The accompanying illustration gives a better idea of their

dwellings than any description, and in these their owners live all the year

round.

mostly used on the island, and a rough

calculation estimates the annual production at one hundred thousand dozen, worth

one dollar per dozen, which is quite a business for a people who carry it on as

they do. The turtle-shell is prepared usually for export, the meat being sent to

the markets of the vicinity in which the turtles are caught. It is quite an amusing sight to see the

habitations of these people, dotting some portions of the bay; and as

it-is almost perpetual summer, their life is not a very

unpleasant one. The accompanying illustration gives a better idea of their

dwellings than any description, and in these their owners live all the year

round.

Puerto

Principe is connected with Nuevitas by a railroad forty-five miles long, and

usually there were two trains a day, between the two places; but as there has

been great trouble on this road, caused by the attacks of the patriots, it is

probable that their running is now very irregular.

Puerto

Principe is, probably, the oldest, quaintest town on the island,—in fact, it may

be said to be a finished town, as the world has gone on so fast, that the place

seems a million years old, and, from its style of dress, a visitor might think

he was put back almost to the days of Colon.

The

road to the town runs through a fine, rolling country, affording many beautiful

views ; and from the hills around the place itself, not only the town, but the

neighboring country, can be seen to advantage. But may heaven help you, 0

stranger ! if you wander to Puerto Principe without having some friends to

depend on ; for, city as it is of nearly seventy thousand inhabitants, it boasts

not of an hotel, and even the fondas

are

wretched. It is, probably, for this reason that the Cubans, as a people, are so

hospitable that they will not allow their friends to go to hotels, and even to

strangers who have been presented to them they insist on showing this

attention.

Lest

I be misunderstood in relation to this matter, I wish to say that it is the

custom in Cuba for one friend visiting the town of another friend to stay with

him at his house, the kindness being returned as occasion demands ; and no one

having the slightest claim to a courtesy of this kind need hesitate to accept

it, either on the plantations or in the interior towns. This can be done without

fear of disturbing the hospitable household of the host, for he gives you what

he has himself, and, as a general thing, every one in Cuba lives in a free,

open-handed way, with abundance of rooms, servants, and an extremely profuse

table. In many cases, too, it is as much a kindness to the giver of the

invitation to accept it as for him to extend it, for the simple reason that

there is not much travel or intercourse on the island, and the stranger, whether

from some other part of the island or from abroad, has news to impart, a novelty

to give, or business to transact with his host. The stranger may be sure

the courtesy is sincere when extended with, " Frankly, Senor, I wish you to stay

with me, and I shall order your baggage to my

house."

Santa

Maria del Puerto Principe is situated in the heart of the grazing country, from

which business it derives its importance. Its streets are narrow and tortuous,

many of them entirely unpaved and without sidewalks ; its buildings comprise

houses of mamposteria,

several

queer old churches, various convents, large quarters for the troops, a tolerable

theatre, and a fine lot of public buildings for government officers. The general

style of architecture, though Cuban, offers many peculiarities to the artist or

antiquarian.

This

town has always been looked upon with suspicion by the authorities on account of

the strong proclivities its people had for insurrection; and its sons have had a

greater or smaller share in almost every revolution that has taken place in the

island. It has now received its baptism of blood in the cause of liberty for "

free Cuba," having sustained a siege, been attacked and almost

starved out, — to what effect, as yet, deponent knoweth not; but many changes in

its people have doubtless taken place since he was there.

Although

there is not much in the actual town to occupy the traveler, the surrounding

country affords fine opportunities for studying some peculiarities of the island

not so advantageously seen elsewhere as here. First among these are the

potreros.

Potrero, in

the Castilian, really means a horse-herd, a pasture-farm; but in the Cuban

dialect, it has a somewhat different meaning. In the early days of Cuba,

when land was plenty and the government liberal in the disposition of it, they

called all grounds or properties, whether belonging to the crown or to private

persons, used for the purpose of sheep-folds or cattle-herding, haciendas

or

hatos.

These

were large extents of ground, of circular form, with a radius of over nine

thousand yards, the centre of which only was marked out, where the pens and

buildings were usually erected. The corral

was

also a circular tract, one-quarter the abovesize, that is to say, with a radius

of four thousand five hundred yards, intended for the care of smaller

cattle, sheep, pigs, etc.; its centre being also marked by the hog-pen, or the

fences of the sheep-folds.

Potrero, in

the Castilian, really means a horse-herd, a pasture-farm; but in the Cuban

dialect, it has a somewhat different meaning. In the early days of Cuba,

when land was plenty and the government liberal in the disposition of it, they

called all grounds or properties, whether belonging to the crown or to private

persons, used for the purpose of sheep-folds or cattle-herding, haciendas

or

hatos.

These

were large extents of ground, of circular form, with a radius of over nine

thousand yards, the centre of which only was marked out, where the pens and

buildings were usually erected. The corral

was

also a circular tract, one-quarter the abovesize, that is to say, with a radius

of four thousand five hundred yards, intended for the care of smaller

cattle, sheep, pigs, etc.; its centre being also marked by the hog-pen, or the

fences of the sheep-folds.

Owing

to the difficulty of always laying out the exact lines, (caused by the location

of woods), the surveyors adopted the method of describing polygons, with a large

number of sides, each of which was equivalent to so many yards. The spaces left

between these polygons, almost circular, were considered as the property of the

crown, and were known as realengos.

But

as time advanced, and the government kept on increasing these gifts,

without any particular reference to the line of demarcation in the land, many

centres of the new farms or folds were fixed in such a manner that, in drawing

their boundary-lines according to their radii, they cut those already

established, one new circle falling within an old one, creating thereby

inextricable confusion, which ended in every man going to law with his neighbor

about his boundary-lines; and from this came the belief that every Cuban had a

farm and a lawsuit.

Many

of these tracts were then, by the decision of the court, divided, and

afterwards, by the will of their owners, sub-divided into small lots,

appropriated for the various uses of cultivating grain, raising cattle, and

fruits, while others were again cut up and laid out in town

lots.

Out

of these divisions came all the different rural establishments known as

cattle farms, farms proper, and small truck-gardens, and which, under the names

of potrero,

hacienda, hato, ganado, finca, and

estancia,

bother

the stranger or the student of Cuban life.

The

largest of all the above is the potrero, where cattle are raised, fed, and

looked after with care; while in the corrales they are left to run wild in every

direction, getting water from the running brooks, and only attended to, from

time to time, by the sabaneros or monteros.

But

the potreros are large places, encircled by walls of stone piled up, or

stone-fences. Not only the cattle of the place are taken care of, but those also

belonging to neighboring ingenios, or farms, are fed and attended

to.

The

raising of cattle is a very profitable business indeed, particularly as no

attention is paid to the fattening of beef, but the cattle are sold just as they

are thought to be fit for market. The consequence is, that it is rarely indeed

that a piece of beef fit to roast is seen,—at least as we know

it.

It

is a great sight to see these immense herds of cattle, scattered over extensive

plains, with here and there largeclumps of palm or cocoa trees affording shade,

while, at regular intervals, long stone walls serve to separate the herds. Many

of the fiercest bulls used in the bull-ring come from this district ; and when

so noted upon the play-bill, an audience is sure to be attracted by the superior

" sport " they offer.

As

cattle-raising plays a very important part in the sum-total of the business

interest of the island, it may not be amiss to give some few facts from late

authorities. The prices, of course, vary in different years, but a fair average

can be obtained by comparing several years' reports. Oxen,

twenty-five to forty dollars. Bulls, twenty to thirty dollars. Cows, twenty to

thirty dollars. Calves, ten to twelve dollars. Sheep are cheap, being sold at

from one to three dollars. Hogs, eight to ten dollars.

In

1827, there were three thousand and ninety-eight

potreros,

and

in 1846, four thousand three hundred and eighty-eight; which is about forty per

cent. increase,— equal to two per cent. per annum. So that at present there must

be between five and six thousand of these places.

Valuing

the cattle at the lowest of the above prices, and calculating from various

reports as to the number of such on the island, it is estimated there is

represented, by the stock of these cattle-places and at the sugar and coffee

estates and smaller farms, a capital of twenty-one millions of dollars. This is

exclusive of horses and mules, too, of which there are large numbers raised upon

the island, the value of which is estimated at two millions of

dollars.

At

one time, camels were introduced into the island, in the hope that they would

answer the purposes of transportation; but they did not do well, for, strange to

say, the smallest insect, the nigua,

that

buries itself in the feet and there pro-creates, utterly ruined all of

them.

At

almost all of these places, the beef is cured by putting it, salted, in the sun,

and it then is known as tasajo

(jerked

beef); and prepared in this way, it will keep for two or three weeks, being used

principally for home consumption, that which is prepared for market requiring

more curing. This is the great article of food amongst the masses of the

population, and is found sometimes even upon the table of the better class, when

no strangers are present. Large quantities of the hides of the cattle are

exported, while the bones are made into " bone black," of which

immense quantities are required by the sugar manufacture of the

island.

From Puerto Principe come, also, some of

the finest horses raised on the island; for, strange to say, in the cities, the

American horse is esteemed most highly, from his greater size and

style.

From Puerto Principe come, also, some of

the finest horses raised on the island; for, strange to say, in the cities, the

American horse is esteemed most highly, from his greater size and

style.

The Cuban horse is not

supposed to be a native either of the island or of these climes,—in fact, if we

believe the accounts of the early discoverers, the animal was not known upon

this continent; for, in every case when the natives first saw a horse, they were

struck dumb with astonishment, showing that they had never seen one

before.

It

is, therefore, suspected that the Cuban horse of to-day, peculiar breed as it

is, is simply the result of some of the Spanish stock transferred to the island

and affected by the peculiarities of the climate in its breeding. At all events,

it is a fine animal now, with a short, stout, well-built body, neat clear limbs,

fine, intelligent eyes, and a gait for long journeys under saddle not to be

surpassed. These horses have sturdy necks, heavy manes, and thick tails, and,

seen on the plains, where they are raised, and before being handled and dressed

they present a very rough and wild appearance. Their gait is something

peculiar, it would seem, to themselves; and on a well-broken horse the greatest

novice in the art of riding need not hesitate to mount.

The

marcha,

or

fast walk, is simply the easiest gait in the way of a walk I have ever seen; and

el

paso, or

the rapid gait of the horse is something like the movement of our pacing horses,

or, as they call it in the Southern States, a single-footed rack, only it is a

great deal more easy. Some of the horses do what is known as el paso gualtrapeo, a

movement

so gentle that a rider can carry a full glass of water without spilling. It is

for this reason that the Cuban horses are so much admired by lady travelers fond

of horseback riding, for they can ride miles and miles without- experiencing the

slightest fatigue. If I were to tell all the wonderful stories about the

performances of these horses, my reader would be incredulous; but this I can

say, that,  day

after day, the Cuban horse will journey from forty-five to sixty miles without

showing the slightest sign of giving out, and on forced rides, seventy to

eighty miles is no unusual occurrence.

day

after day, the Cuban horse will journey from forty-five to sixty miles without

showing the slightest sign of giving out, and on forced rides, seventy to

eighty miles is no unusual occurrence.

The

price varies, according to circumstances, from sixty dollars to even as high as

one thousand dollars for the very finest bred, and it is amusing to see with

what care those owned by wealthy people are treated. Owing to the sticky nature

of the mud of the country roads, it has been the custom to plait the tails of

all the horses (the end being fastened to a ring in the cantle of the' saddle),

and to crop the manes. But in the cities, especially, is great display made in

plaiting the tail with fancy ribands, and the mane is trimmed with mathematical

precision.

Judging

from experience, I should say that all Cuban horses were good, even-tempered

animals; for, though I have backed many wild and spirited ones, both in town and

country, I never found one that was really vicious, and I never saw one raise

its foot for a kick at a human being. The Cubans explain this by saying that the

horse is one of the family, as in town he is kept in some portion of the

patio, usually near the kitchen, and in the country he is treated with

even more familiarity.

One

of the first things in a Cuban house that strikes the stranger with its novelty

is the guayaba con queso, or guava with cheese, which may mean

either guava jelly or marmalade; and from this universal custom, one wishes to

know what is this guava they make so much use of ; and as Puerto Principe is a

place noted for its manufacture, I will give here a description of

it.

In

some of the towns of Cuba, such as Trinidad, Santiago de Cuba, and Puerto

Principe, there is a class of women remarkable for their beauty, whose race it

would be hard for the stranger to tell, with any degree of certainty,— some

appearing even lighter in color than Cubans ; others, again, like the

far-famed octaroons of Louisiana; and still others, of the light mulatto

order,—all resembling each other, however, in the wonderful blackness and

brilliancy of their eyes, the jet of their hair, and a certain indescribable

grace of outline and movement of figure, having in it a dash of that voluptuous

languor that we believe peculiar to the Orient.

Who

they are, and what their fathers and mothers have been, it would be hard to say.

Some of them, however, claim to have " gentle blood " running in their veins,

and, if appearances are worth anything, with good reason. Be that as it

may; they are the seamstresses, very, often the lady's

maids, but more frequently the manufacturers of the delicious pre-serve known as

" Jalea " and " Pasta de

Guayaba."

The

dulce or sweetmeat of guava, then, is of two kinds, — the jelly, a pure,

translucent, garnet-colored substance, similar to our currant jelly ; and the

marmalade, an opaque, soft substance, similar to good quince marmalade, and of

about the same color, or darker.

Both of these are made from the same

fruit, though prepared in a different way; and there are also two kinds of the

fruit,— one known as the guayaba de Peru, which is very scarce, and the

other, guayaba cotorreras, the common red apple-bearing tree, which is

the one most found in Cuba ; the fruit of the former being of a greenish color

in the inside, while that of the latter is either red, yellow, or

white.

Both of these are made from the same

fruit, though prepared in a different way; and there are also two kinds of the

fruit,— one known as the guayaba de Peru, which is very scarce, and the

other, guayaba cotorreras, the common red apple-bearing tree, which is

the one most found in Cuba ; the fruit of the former being of a greenish color

in the inside, while that of the latter is either red, yellow, or

white.

The

fruit is small and edible, having a fragrant but peculiar odor, and a sweetish

taste; and the making of the jelly is an extremely simple operation, as

follows: The fruit is cut in halves, and separated from the seeds, then gently

stewed; then the sugar, thoroughly boiled to a syrup, is cleared. The guava is

now strained through a bag, and the juice only being united with the syrup, it

is all boiled until it reaches a proper state of consistency, when it is taken

out, put into moulds of the different sized boxes required, and allowed to cool

and get firm, when it is placed in long, shallow boxes of various sizes, lined

with paper, then closed up, papered to keep out the air, and labeled for

market.

The

paste is made in the same way, except that only the seeds are taken out, and the

whole fruit incorporated with the syrup is used to make the marmalade, which by

many is considered the richer for that reason. To any of my readers who

have ever tasted the guava jelly it needs no recommendation; but to those who

have not, and who wish a " new sensation," I advise them to try it,

being careful, however, to buy the small, flat boxes, which are the best, the

round boxes usually being filled with very poor stuff. Large quantities of this

sweetmeat are exported each year, and there are many manufactories of it in

Havana; the best, however, comes from Puerto Principe and

Trinidad.

From

Puerto Principe there is no way of reaching Havana except by steamer, or else by

hiring horses and a guide, and striking off on the camino real for a very

long and tedious journey through the interior to some of the towns connected by

railroad or steamboat. I, however, having circumnavigated the island, and

crossed its interior, east and west, prefer the more easy and rapid way of the

railroad to Nuevitas, and thence by steamer to Havana, which, after some three

months' absence, I reach in the hot days of May. I say hot, but I

think I owe the island an apology; for the hottest days that I ever experienced

there were nothing in comparison with the terrible days of intense heat of the

past summer; and any man who can exist through such a season, is prepared, I

think, to live comfortably in any climate in the

world.