SOMETHING ABOUT CUBA, ITS HISTORY, ITS CLIMATE, ITS PEOPLE.

By T. B. Thorpe

I.

THE Island of Cuba in size is nearly equal to England proper (without the principality of Wales), being seven hundred and eighty miles in length, and about fifty-two miles in medial breadth, containing a superficial area of forty-three thousand five hundred square miles, being nearly equal in extent to all the other West India Islands united. Columbus supposed Cuba (at the time he visited the Isle of Pines, associated with Cuba) to be a continent, and it was so regarded until circumnavigated by Ocampo, in the year 1608.

In the early times of the settlement of the West India Islands, San Domingo was the most known, and received the largest share of attention. Cuba attracted but little notice in Europe, until Cortez made a base of operations, in his contemplated and consummated attack on Mexico. It will be perceived its first appreciation was for its military command of the surrounding coasts. Subsequently, in necessary imitation of Cortez, the Prince de Joinville concentrated his fleet at Havana, preparatory to his attack on Vera Cruz, and to Havana he returned after capturing San Juan de Ulloa.

The importance of Cuba does not therefore arise solely from its great productive wealth, nor from the demand its inhabitants make upon the productions of other peoples, but it is largely founded upon its admirable position in commanding the entrance to the Mexican Gulf, Havana being situated exactly where the carriers of commercial enterprises must cross each other's paths in their intercourse with Mexico and the Southern United States. It is a wonderful instance of the sagacity and statesmanship of Thomas Jefferson, that he should have written, nearly fifty years ago: "I candidly confess that I have ever looked upon Cuba as the most interesting addition that can be made to our system of States, the possession of which (with Florida Point) would give us control over the Gulf of Mexico, and the countries and isthmus bordering it, and would fill up the measure of our political well-being."

Its importance, as the “key to the Gulf," will be still more perfectly understood, when we recollect that Cuba is ninety-five miles from the nearest point of Jamaica; fifty miles from Hayti; one hundred and twenty miles from the coast of Tobasco and Yucatan, in Mexico; and one hundred and fifty miles from the coast of Florida.

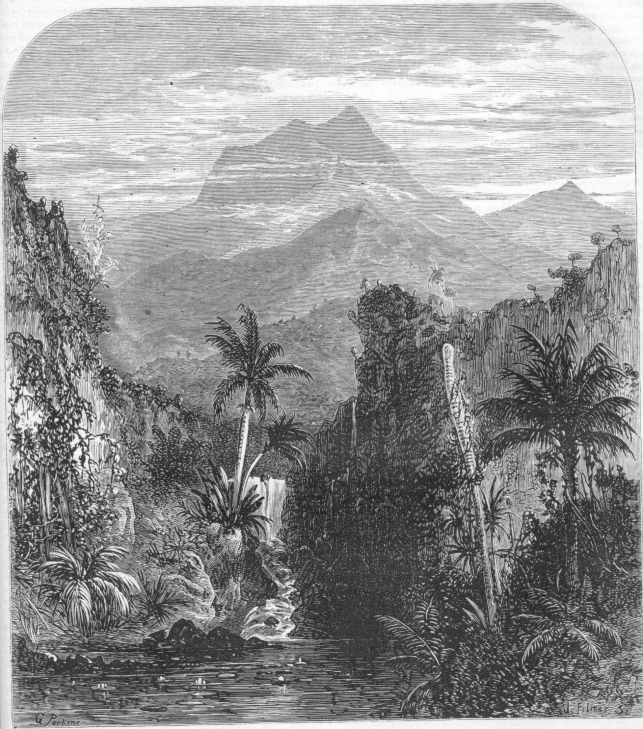

VIEW IN THE SIERRA DEL COBRE, CUBA.

|

The Gulf of Mexico, almost an exact circle, has a shore line of nearly six thousand miles, and the outlet of this vast field of commerce is through a narrow passage running along the southern shore of Cuba, and within a few miles of her best harbors and fortifications. It is, therefore, certain, that whatever people hold Cuba, if they have at command the resources natural to the island, and the desire to do so, they could make the commerce of the western world pay tribute, and embarrass our legitimate rule in the Gulf by treaties and assistance from European nations. And this has already been done, for, when the fleet of Sir Edward Packenham operated against New Orleans, and was compelled in a crippled state to retreat from the coast of Louisiana, it fled to Havana for succor, and, but for this place of refuge, never would have reached Jamaica, its original port of embarkation.

But we do not propose in our slight sketch to treat of the military and political characteristics of Cuba, we allude to them only incidentally, and pass on to such description of its scenery, agricultural resources, and the social life of its inhabitants, as the best authorities at our command and our personal observations will supply.

The past of Cuba is history, and, under any and all circumstances, soon a new and varied future must open upon her; and we have no doubt that the results will be advantageous to her best interests and true development. Up to this time, one of the most favored spots on the globe, abounding with great mineral, agricultural, and maritime resources, has been cramped in its natural growth as much as if it were the foot of a Chinese belle, yet, in spite of the bandages of every possible restriction, Cuba has surpassed any given portion of the world in what it has done, and in what it promises as the reward of labor—for, in accordance with her population, and in spite of her misgovernment, Cuba, today, presents a wonderful example of material prosperity. If these things be, with a parent government heartless and oppressive, and subjected to the consequent evils flowing therefrom, what will the “Queen of the Antilles” be, when her mountains, her valleys, and her beautiful and commodious harbors, are in the possession of even a comparatively free and untrammelled population, who will develop her vast natural wealth, and make it contribute to the happiness of the producer, instead of the pride and squanderings of an unsympathizing aristocracy?

The climate of Cuba, especially in the suburbs of Havana, is considered the most salubrious of any of the West India Islands, with the possible exception of Porto Rico. At Ubajay, fifteen miles from Havana, the thermometer in fair weather has gone down to zero. It is impossible to realize the fragrant delightfulness of early dawn, or the exquisitely-soft coolness of the evening, in this wonderful island of the tropical seas. After the intense heat of the day, the sea-breeze seems to refresh and strengthen the very spirit of life, the pulse beats fuller and clearer, producing sensations to be enjoyed, but never described. In the interior of the island there is a variety of temperatures, for the mountains favorably modify any intense heat. Thus Nature in many ways overcomes difficulties for the happiness of man, and thus it is, however hot the day may be in those southern latitudes, in the evening and the morning there prevail refreshing winds; while in the mountainous regions the deposition of dew is so plentiful at nightfall that it takes the place of copious showers in modifying the heat and preserving vegetation.

That outdoor labor for every class of people is not impossible in Cuba, we know; for two-thirds of the population, including slaves and coolies, work the livelong day in the unqualified rays of the sun, and do this under its most trying circumstances. What would be the effect of labor in Cuba, supplied with proper clothing, wholesome food, a reasonable number of hours for work, and a comfortable lodging at night, is still to he tried.

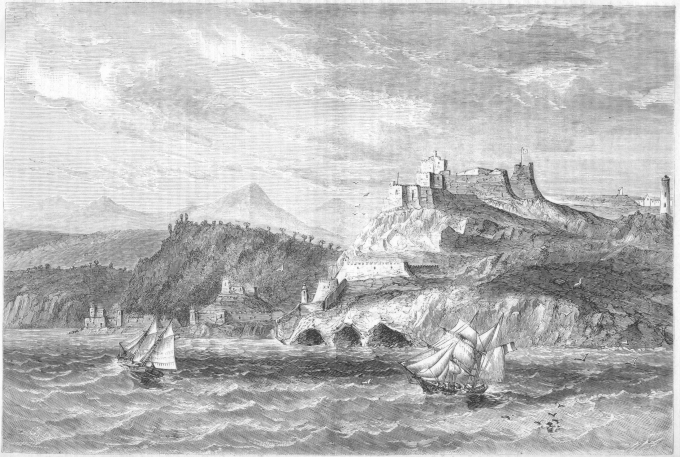

In approaching Havana from the sea, a chain of undulating mountains runs from east to west, until lost in either horizon. On each hand, as you approach the harbor, the land is gently elevated, and covered with grassy, luxuriant vegetation. The signal-tower and light-house combined, which overtops the high walls of the defences, which immediately lie at the mouth of the harbor, is an object of great interest to the novice in sea trips, for, with the desire to get to land, is added the intense curiosity to see the sights of Havana. On the first occasion of our beholding the red-and-gold-slashed flag of Spain, the sun was rapidly sinking into the waves of the great Mexican Gulf, and we watched the flag and the sun with painful solicitude, for we knew that they would sink out of sight together, and we also knew that, if they did this before we reached the harbor, we should be obliged to remain at sea all night.

In our anxiety and impatience to make headway, it seemed to us as if the huge engine of the steamer had lost its propelling power. Passengers, in nervous crowds, stood upon the deck, and wished and hoped ; but, alas ! all our aspirations were bound to be disappointed, for suddenly, a light cloud of smoke ascended upon the clear atmosphere, the low but suggestive sound of a heavy, but distant piece of artillery echoed along the Cuban shore, and sun and flag disappeared together as simultaneously as if both were under the military discipline of the now dethroned Isabella.

At the same instant the engineer's bell of the steamer's engine gave a significant tap, and the huge machinery stopped its rapid motions as if exhausted, and the “skipper” announced that “we had to ride in the open sea until morning dawned.”

The same rules that were established two centuries or more ago by the jealous Spaniard, to guard against the sudden invasion of freebooters, have continued in force against the peaceably-disposed passenger-ships of these modern times.

The atmosphere of Cuba, as everywhere within the tropics, is so unpolluted, so thin, so elastic, so serene, and, save by experience, so inconceivably transparent, that every, star and planet in the heavens seemed to be boldly defined; you can see around and behind them; they actually stand out in the clear blue, while the heavenly constellations are more brilliant than in the temperate latitudes. In this night-watch we saw the north-star and the great polar bear skirting along the horizon. And there were constellations unknown to northern skies, with the myriads of stars forming the milky-way, making not a dim, just-perceived light, but absolutely flaming through eternal space. All this was some comfort to our disappointed feelings, and lessened somewhat the indignation we felt at the workings of the miserable policy and old fogyism of the Spanish authorities.

“Couldn't our Government make a treaty that would break up this absurd rule, which might have been well enough for Drake and his myrmidons, but should not be enforced to the keeping of a peaceable merchant on the sea all night, in sight of a comfortable harbor?" said we at last to the captain.

“Don't think a treaty could be made,” he replied, emphatically.

“Do you mean to say that the powerful United States, which could send a single iron-clad into that closed harbor of Havana yonder that would knock Morro Castle into Hinders in a few moments, that such a Union, if it insisted upon it, could not have such abominable laws repealed?”

The ground swell, or some other kind of swell, was now making us sick, and consequently ill-natured, and this, too, in spite of the fine atmosphere, the starry constellations of the altar, the cross, and the River Eridanus.

“We mean to say,” returned the captain, speaking with the authority of the quarterdeck, “we mean to say, that Spain will not alter her laws regarding the entrance and exit of her harbors, or in any other matter, unless forced to do so by the argument of war!”

Just at this moment, at the very spot where we knew was Morro Castle, we saw a column of smoke, which, in the clear atmosphere we have so much admired, rose like a signal from some savage chieftain's camp. This column grew taller and taller, and nearer and nearer, and finally began to stretch away toward the west.

“What's that?”said we to the captain, very much surprised at this evidence of life exhibited in what should have been, by Spanish orders, “a dead place.”

“Why,” said the captain promptly, “that smoke is from Liverpool coal, and, if you could see the fire it comes from, you'd find the boilers of a confederate blockade-runner that plies between a Texas port and Havana.”

And, while we were looking and speculating, we saw, far away on our right, what might have been other signal smokes; long, straggling lines that crept and curled along the horizon, and then up into the midnight sky, like wounded serpents, and these were from other blockade-runners that were coming from the mouth of the Rio Grande, laden with cotton—then more valuable than gold—all of which contraband vessels, at night or by day, passed unchallenged into the harbor of Havana.

“I declare,” said the captain, with some affected surprise, “the Cuban Spanish officials have been bribed to do this; but it won't pay to buy our way in ; so, in sunshine or storm, breeze or hurricane, we must stay out here all night.”

But morning came at last, bright, cheering, and early. It was hard to say when the stars melted away, or how the heavens were brighter because the sun was turning every thing into yellow and gold. Another booming sound officially informed the Cubans of the break of day, and the red flag again trembled over Morro Castle, and our gallant steamer, as if refreshed from repose, now proudly and swiftly moved toward the entrance of the harbor.

In a few moments we were between the long lines of fortifications, introducing us to rock-bound shores, that for nearly three-quarters of a mile are not four hundred yards apart. No engineer could have arranged them more perfectly for defence or safety, and the natural effect could not be more picturesque.

On one side, the fortifications, hewn out of the dark-gray rock, were surmounted by parapets that bristled with artillery, and animated by the appearance of soldiers and sentinels in light uniforms, who were constantly moving about. On the opposite side and along the shore there spread out the city of Havana, not sombre, like London, nor white, like Paris, but party-colored, like Damascus, and equally flaming and brilliant in the hot sun, the fronts of the houses, owing to some peculiar taste of the inhabitants, being frescoed with the brightest yellows, pinks, and azure blue, with the roofs red with tiles—the whole made more noticeable by contrasts with the deep coppery green of the overtowering palms, and other luxuriant tropical vegetation ; in the harbor were innumerable gayly-colored gondolas ; the ships were anchored in the middle of the stream, being only allowed to communicate with the shore through the lighters and small sail-boats that everywhere meet your gaze—the whole effect giving a peculiar character, and a romantic life, unlike any other city in Europe or America.

Our vessel, under the guidance of the Spanish pilot, finally reached her berth in the middle of the harbor, and, before the heavy anchor was fairly embedded in the earth, the sail-boats came circling round us from the shore like so many huge albatrosses bent on prey.

A few years ago, passengers could not go ashore at Havana without passports, which, when fairly settled for, cost some five dollars in gold. But this is not so now, though occasionally an unlucky traveller hands this amount over to some one of the numerous officials—always in sight just as a countrymen, it is said, will sometimes, in New York City, give a “sharper" twenty-five cents for going into the City Hall Park. But you go ashore, of course, and possibly have a sail of a mile or more before you reach the common landing, which is opposite the principal gate of the river-front of the city. You look up; and see a coat-of-arms over the grand entrance, once familiar, when we used Spanish silver coin, prominent upon which were the pillars of Hercules. The first impression made upon an American is, that there is an enormous number of semi-military policemen. The ship was spotted with them the instant it arrived in the harbor, and in the city you find every alley, lane, street, wharf, and stair, guarded by them, many armed with a light musket, and all set off with a saffron-colored visage, contrasting strangely with a thin white linen coatee, held together at the shoulders by immense yellow worsted epaulettes. But these guardians of the peace and safety of Havana, such as they are, are respectful to well-disposed strangers ; their business is to look most exclusively after the native population.

The streets inside the walls, as a rule, run at right angles, and are very narrow ; the best are badly paved, and undrained. The houses suggest that they have all at one time or another been used as fortifications, they have such an appearance of unnecessary strength, and are so covered over with heavy iron gratings. They are seldom more than two stories high, and, in the most populous streets, have awnings suspended across the highway, from ropes fastened to the heavy parapets that surmount every building ; which arrangement is grateful, in securing you somewhat from the effects of the noonday sun.

Every thing, to an American and a stranger, is intensely odd and very interesting. If you are in the principal street, you find the stores small, and a casual display of goods apparently a secondary matter. You look up and down, and are surprised in not seeing a lady in sight—you catch the bright eyes of what you suppose to be one, peeping from behind some jalousie, but it is a suggestion, not a positive fact. The men you meet, if not of the military, are all dressed in white pantaloons, grass cloth jackets, and panama hats—they know you are a barbarian and a “fillibuster" (synonyms for a citizen of the United States), from your thick clothing and self-conceited stare.

A woman at last—a stout one—dressed in black silk, queer-looking flat hat, no hoops on, great sash around the waist, and surprisingly large feet. You think you have always heard the Spanish women have small pedestals. You look again, and it is a portly priest; and as you see a great many of them afterward, you make no second mistake as to their sex or business.

Gradually growing self-possessed, you reach a street occupied wholly by private residences. You observe that the houses have no sashes to their windows, but, instead, heavy iron bars and gratings. Delicate lace curtains inside, and rich, heavy furniture, satisfy you they are not prisons. But their Moorish, oriental expression, gives them an intensely dull exterior. You think better of them when you discover a group of senoritas busily engaged in gossiping and smoking cigarettes. They let you stare at them without displaying the least annoyance—they rather like it, or they don't know it—you will never be able to tell which.

We have said the streets are very narrow, and here comes a cabriolet, or bullock cart, in common use in the country. It is the rudest wheeled vehicle you ever saw, and the animals drawing it have a wild, shaggy look, that is perfectly demoniac. The fellow driving is a first-class African slave, mounted upon a lot of old garden “truck" he has for sale. The African's dress consists of a pair of pantaloons, with a scarcity of cloth that would please an opera-dancer; his shirt is included in a well-worn suspender, else he has none. No covering for head or feet ; but, slave as he is, he's a Spanish slave, or rather, according to his race, he insensibly imitates the manners of his superiors ; and, mounted upon his moving throne, he puffs out the smoke of his cigarette with an air that no one but a grandee of Castile can surpass.

But, ho ! the vehicle approaches, the wheels spread so wide that they travel in the gutters each side of the street, and the huge hub projects over the twenty-inch-in-width side-walk, more than half-way; we flatten ourselves against the dead wall, and just escape being brushed from the narrow walk into, the street.

Until within a few years, to use an equivocal phrase, the hackney-coaches of Cuba were volantes. They are the most grotesque, illy-constructed vehicle, their uses considered, that can be imagined; where the fashion came from we have not learned. Their shape and appearance can only be fully realized by personal inspection. The wheels are about six feet in diameter, the shafts vary from fifteen to twenty feet in length. The sedan-chair for the passenger is placed on the shafts, a few feet in front of the wheels, and then a very small horse or mule is fastened to the shafts opposite. The propelling power is mounted by a negro, à la postilion. These fantastic vehicles are often of costly construction, mounted with silver, and adorned with every possible ornament to make them attractive. But within a few years the open carriage, common to New York and London, have become quite familiar in the streets of Havana, and are gradually, at least for strangers' use, displacing the old, queer, characteristic volante, which no doubt came into fashion by some law that prevented common people from riding in four-wheeled vehicles, this being a luxury only to be indulged in by the grandees and royal personages of Spain.

MORRO CASTLE, AT THE ENTRACE TO HAVANA.

|

After due study of Cuban architecture, and after an examination of the best old residences, you find they are all built upon one unvarying plan, that of a hollow quadrangle ; flat roofs are universal. A lofty portal opens to the entrance hall, which hall serves for a coach-house for the volante, and a store-room for things not immediately needed in the house. The interior court is surrounded by galleries, attached to which are the sitting, public, dining, and bed rooms, with the general staircase leading to the landings. The servants' rooms and kitchens occupy the first story, and frequently shops of the meanest appearance are seen opening on the street, above which are magnificent suites of apartments. The style suggests a dull grandeur, an antique and almost vandal character, which deeply impresses the stranger ; but with all this barbaric magnificence which one sees occasionally exhibited, there is, apparently, a great deficiency of comfort and convenience. And any regularity of style seems never to be thought of, for, close beside an elegant arcade, with frescoed walls, stands a ruined, deserted old building, the very representative of hopeless desolation.

If you are permitted to visit the interior of these imposing dwellings, you will find that the principal apartments are barely, though sometimes richly, furnished. Among those less wealthy than the privileged orders, old-fashioned, high-backed chairs, covered with leather, and gilt nails, are great favorites ; a table or two of the same style, with a hammock intersecting the room diagonally, and nearly touching the floor, complete the ordinary outfit. Bedrooms seem to be located without much regard to privacy, and, in many, beds are never seen ; their place is supplied by stretchers, or cots, and hammocks, which, when desirable, are folded up and put away during the day. The Cubans, unaffected by foreign ideas, live upon a few very simple dishes, and are satisfied with two meals a day. A great variety of food cannot be obtained. The celebrated “olla podrida," composed of fowls imported from the United States, with some beef, pork, onions, saffron, pepper, and garlic, is very wholesome, and suited to the climate and resources of the people, who esteem it a national dish.

Havana, especially in house-rent, boarding, clothing, indeed every necessary for the support of life, and to promote comfort, is the most expensive place in the world.

Here it is perhaps necessary to say, that the saddest chapters of suffering that could be written would be the histories of confirmed invalids coming from the Northern States, seeking health in "the balmy air of these tropical climes." Accustomed to the careful housekeeping and domestic arrangements of their northern home, and sustained by an invigorating climate, they find themselves suddenly in Havana, deprived of even a comfortable retiring room, and without the necessary convenience of even a bed to lie upon. Every dish, except otherwise ordered, is reeking with red pepper, onions, or garlic ; the language and habits of the common people are strange and repulsive ; and, mean time, the climate, enervating and exhausting to the most vigorous constitutions, completes the disaster ; and the poor, disappointed seeker of health learns, when it is too late, the sad mistake that has been made by the consumptive searching a warm latitude for health.

We saw one of these wretched people hoisted by the aid of a mattress upon the deck of our departing steamer. There was apparent death in the eye, and in the emaciated frame. It was a desperate effort to reach home and die among friends and kindred. Presently the steamer moved out of the harbor, that was literally as hot as an oven. The cool sea-breeze fanned the brow of the sinking one; the pure, fresh air acted as an elixir ; the eye brightened, the voice returned, the hand had the power to give an affectionate return for the friendly grasp. The cool night air set in, and the invalid, like one escaping from an exhausted receiver, wept and sighed over the suffering endured in the sad climate and surroundings for invalids, common to all Cuban resorts.

|