The Life and Death of Ignacio Agramonte

La Vida y Muerte de Ignacio Agramonte

This short pen-and-ink graphic publication (18 6¼" x 4½" full page panels with captions) was published in Camagüey, Cuba, in 1941. The copy from which this electronic edition was taken is missing its cover and first few pages, so its author(s) and publisher is not known. The artist has signed each panel “R. Calindo.” It is not known if he or someone else wrote the Spanish text. It was translated to English in 2016 by José Prats.

Ignacio Agramonte y Loynáz was a Cuban revolutionary from Camagüey who played an important part in the Ten Years’ War (1868–1878), one of the wars of independence against Spain. Born in 1841, he died in 1873. He was 31 years old.

Because of the missing pages, we begin with the third panel. It is 1851.

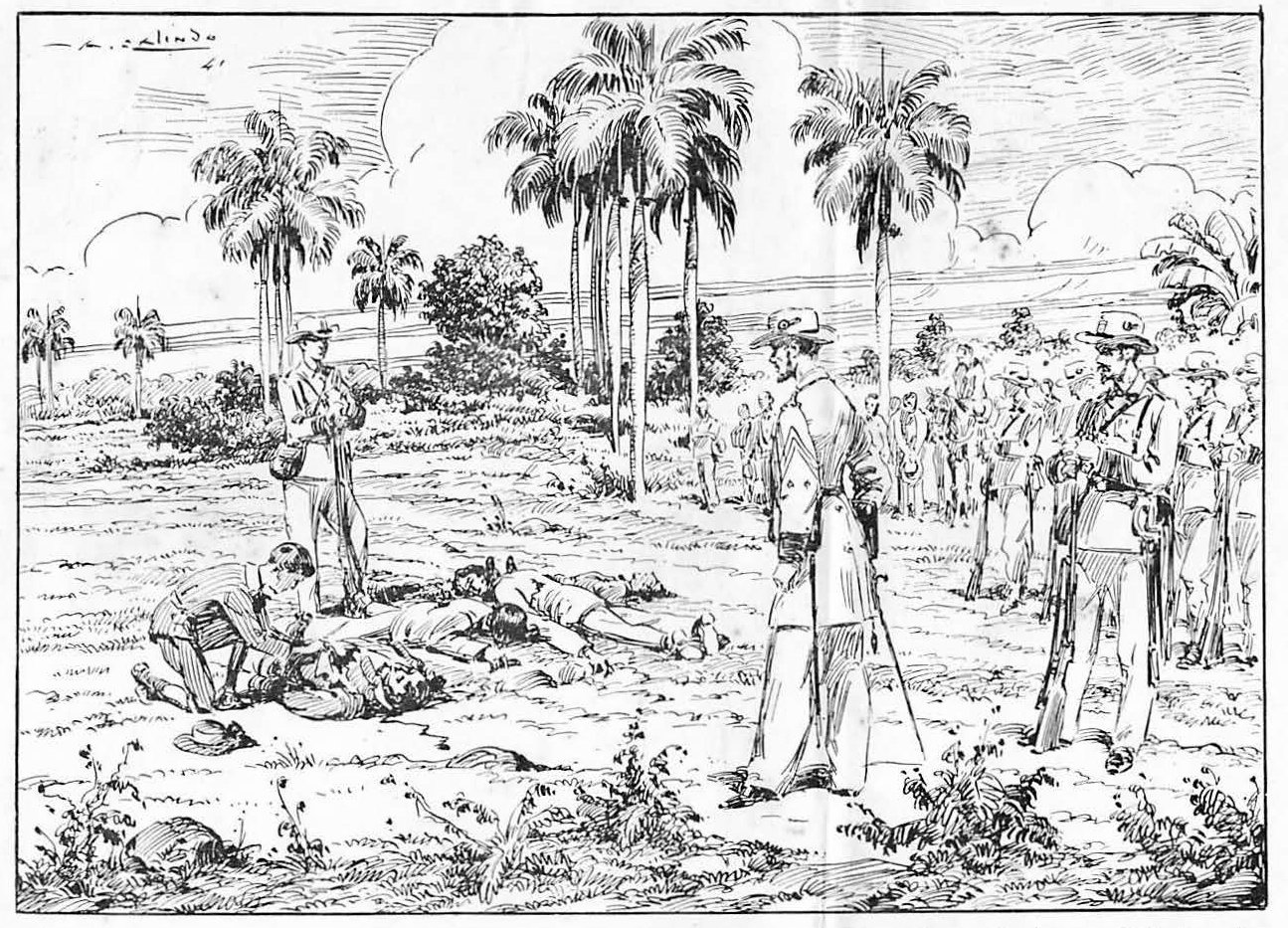

When Agüero, Benavides, Betancourt and de Zayas were executed on the savannah at Méndez Creek, Ignacio was 10 years old; but patriotic feelings were already well formed in him. With his parents’ permission he went to see the bodies of four martyrs. In front of them that child, obeying an irresistible impulse, took out his handkerchief and dipped it in the blood of Joaquín de Agüero. Original caption: Al ser fusilado en la sabana de Arroyo Méndez, Joaquín de Agüero, Miguel Benavides, Tomás Betancourt y Fernando de Zayas, tenía Agramonte 10 años; pero ya alentaba en él, la emoción patriótica y obtuvo de sus padres permiso para ir a ver los cadáveres de aquellos mártires. Frente a ellos, aquel niño, obedeciendo un irresistible impulso, sacó su pañuelo y lo mojó en la sangre de Joaquín de Agüero. |

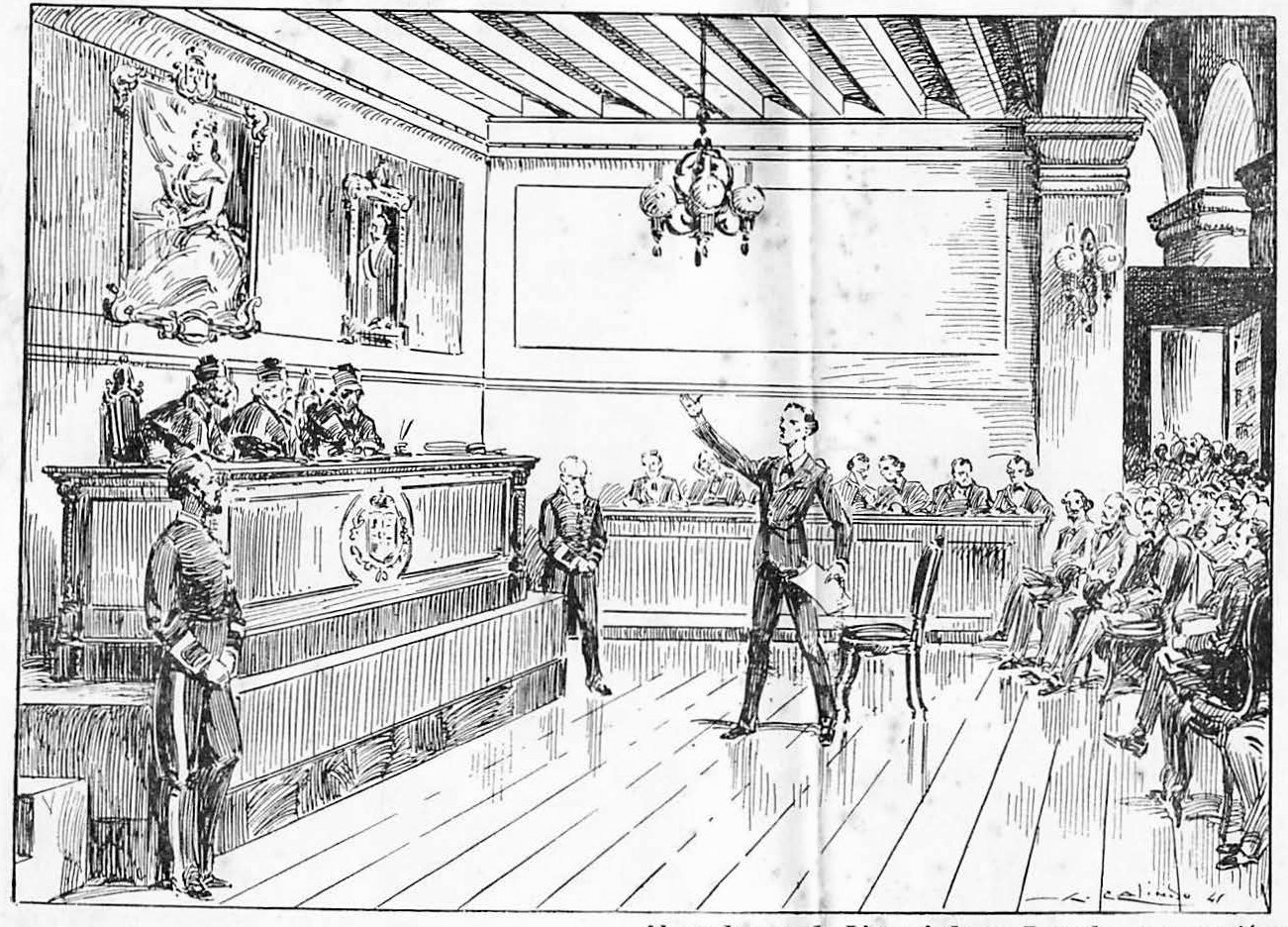

When he graduated with a degree in Law, he gave a discourse at the University—then located at the Santo Domingo convent—a vibrant song to liberty and individual rights. His speech attacked the Spanish colonial regime and summarized the spirit of the Cuban revolutionary. About his talk Antonio Zambrana said “It was like a clarion call. It could be said that the floor of that old convent trembled when he spoke. Afterwards, the president of the tribunal lamented that had he known what Ignacio was going to say he would have prohibited the lecture.” Al graduarse de Licenciado en Derecho, pronunció un discurso en la Universidad, entonces situada en el Convento de Santo Domingo, que era un vibrante canto a la libertad y a los derechos individuales, ataque al régimen colonial y síntesis del espíritu revolucionario cubano. Y sobre él dijo Antonio Zambrana y Vázquez: “Aquello fué como un toque de clarín. El suelo de todo el viejo convento de Santo Domingo se hubiera dicho que temblaba. Lamentándose el Presidente del Tribunal de no haber conocido previamente el discurso para haber prohibido su lectura”. |

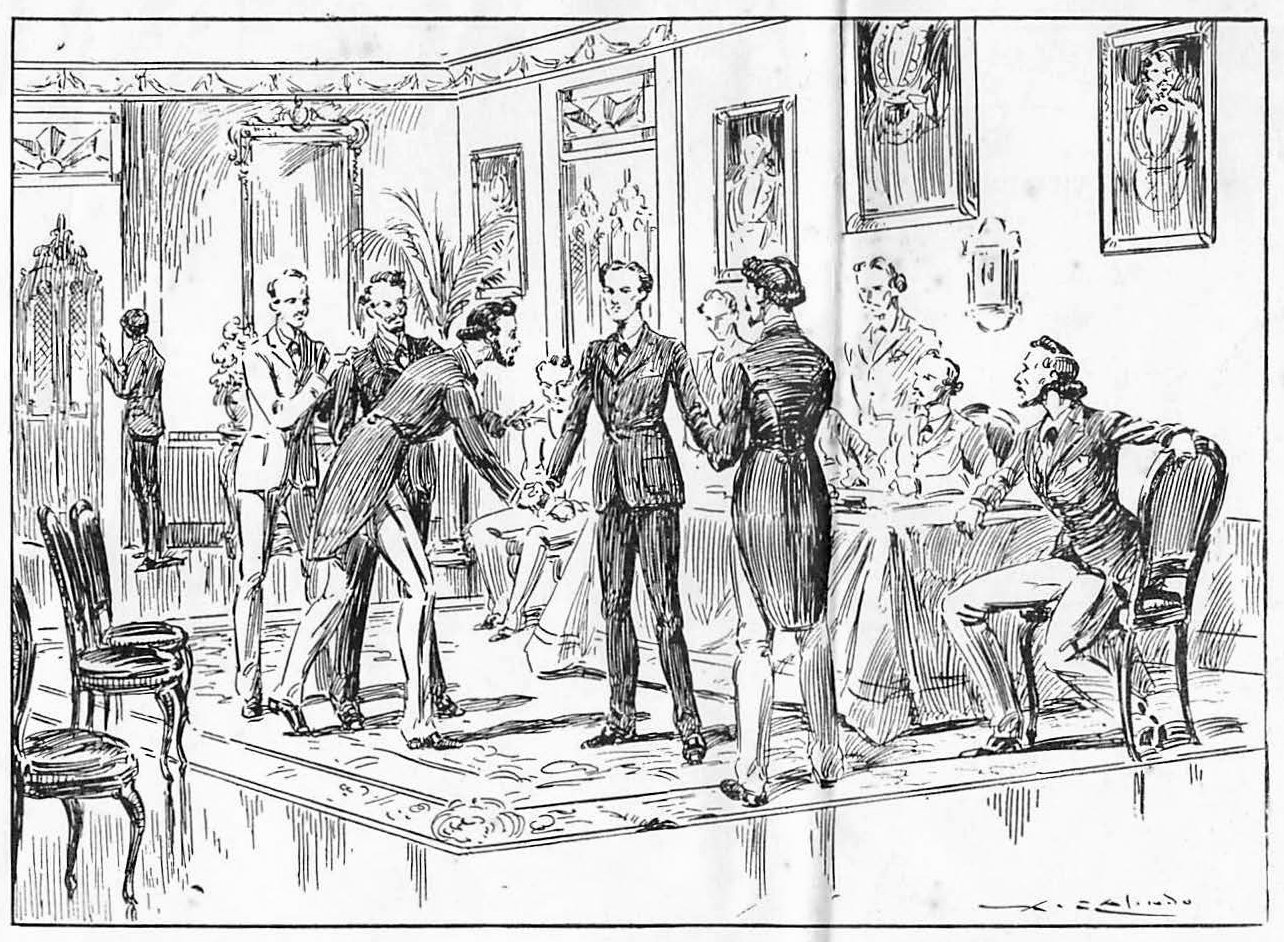

Shortly thereafter Agramonte started attending meetings of conspirators, especially at Masonic Lodges. His young figure, his vigorous character, and his moral integrity stamped itself in their plans. His enthusiasm and militant ardor was such that quite quickly Cubans felt like an invaded and occupied populace. The year 1868 was in progress and the august moment at the Demajagua sugar mill was approaching. Muy pronto Agramonte comenzó a frecuentar reuniones de conspiradores, especialmente en Logias Masónicas, en las que su figura juvenil, su carácter vigoroso, y su integridad moral, imprimieron siempre a tales planes el entusiasmo y el ardor bélico de que muy pronto se fué sintiendo invadido todo el pueblo cubano. Transcurría ya el año 1868 y se aproximaba el momento augusto del Ingenio de la Demajagua. |

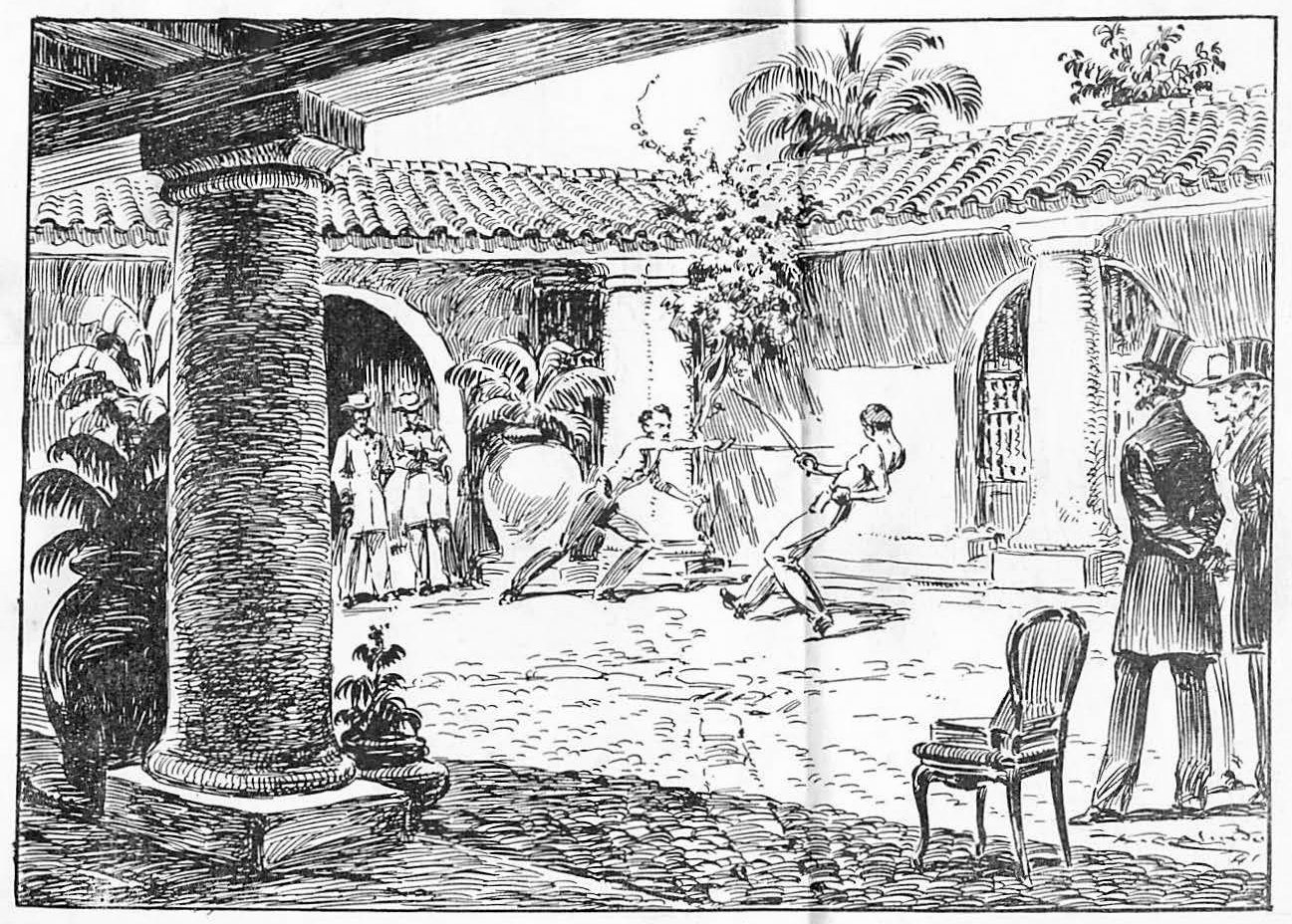

During the carnival of San Juan in Camagüey, at one of the dances, a Spanish official offended a young camagueyan girl, the daughter of Manuel de Quesada. Agramonte challenged the Spanish Commander to a duel. Both were wounded. Already in Camagüey enmity divided the Cubans and the Spanish into separate groups. Con motivo de las fiestas del San Juan y en un baile, un Oficial español ofendió a una joven camagüeyana de la familia de Manuel de Quesada. Agramonte requirió al Comandante español y surgió el duelo en el que ambos se hirieron. Ya en Camagüey existía la enemistad profunda que dividía en grupos distintos a cubanos y españoles. |

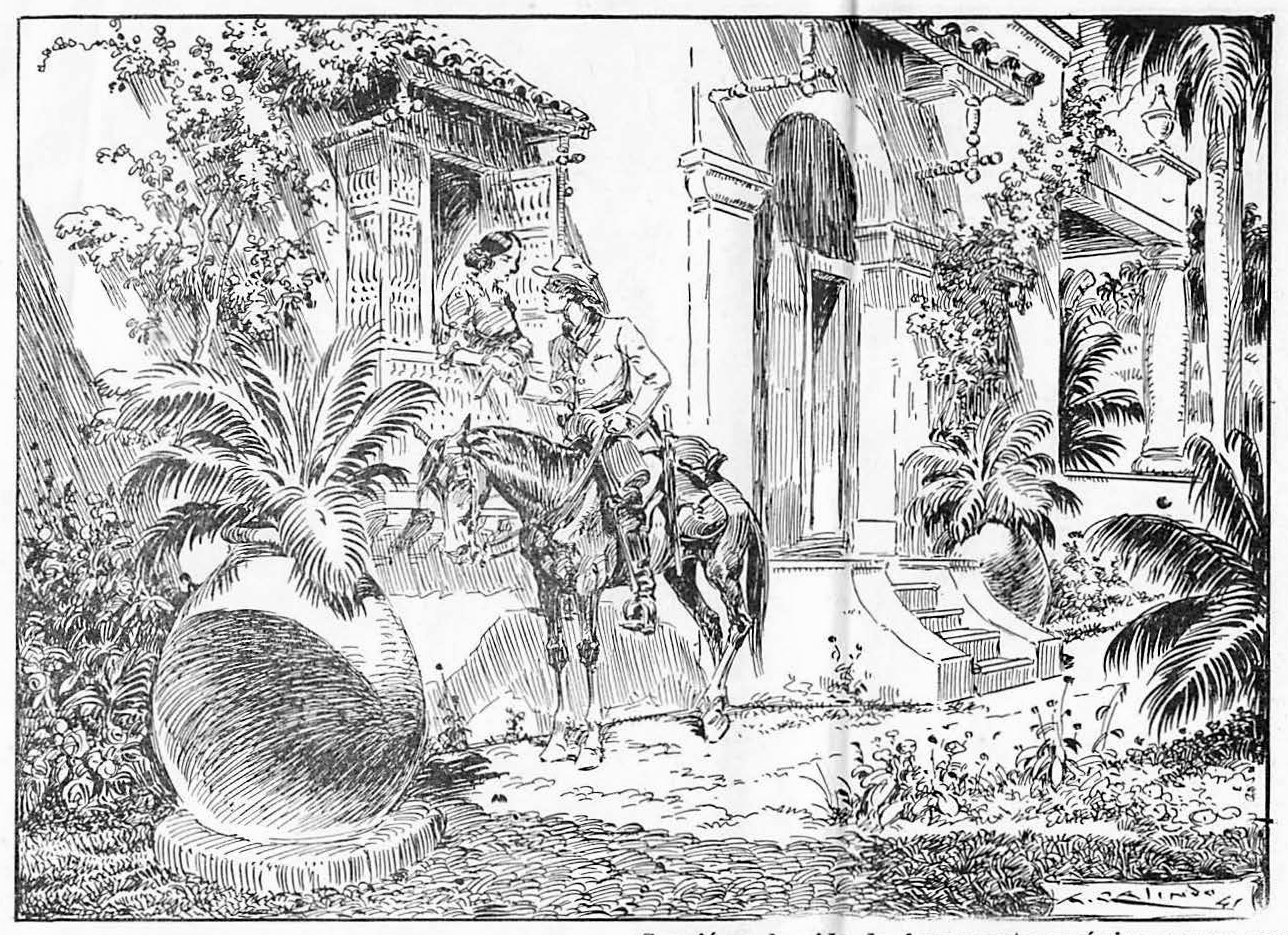

There arose in Agramonte’s life his only great love, Amalia Simoni, a woman of extraordinary beauty and herself imminently worthy— for her valor and patriotism—of the virtuous hand of her husband. It was a passionate idyll into which war placed notes of emotional tragedy. The letters they wrote to each other constitute documents that contain true jewels of romantic writing and noble examples of love and self-denial. Surgió en la vida de Agramonte su único y gran amor: Amalia Simoni, mujer de extraordinaria hermosura y digna, por su valor y patriotismo, de la figura excelsa de su esposo. Fué un idilio apasionado en el cual la guerra puso notas de trágica emoción y las cartas que entre ambos se cursaron constituyen documentos que encierran verdaderas joyas de romántica literatura y nobles ejemplos de abnegación y cariño.. |

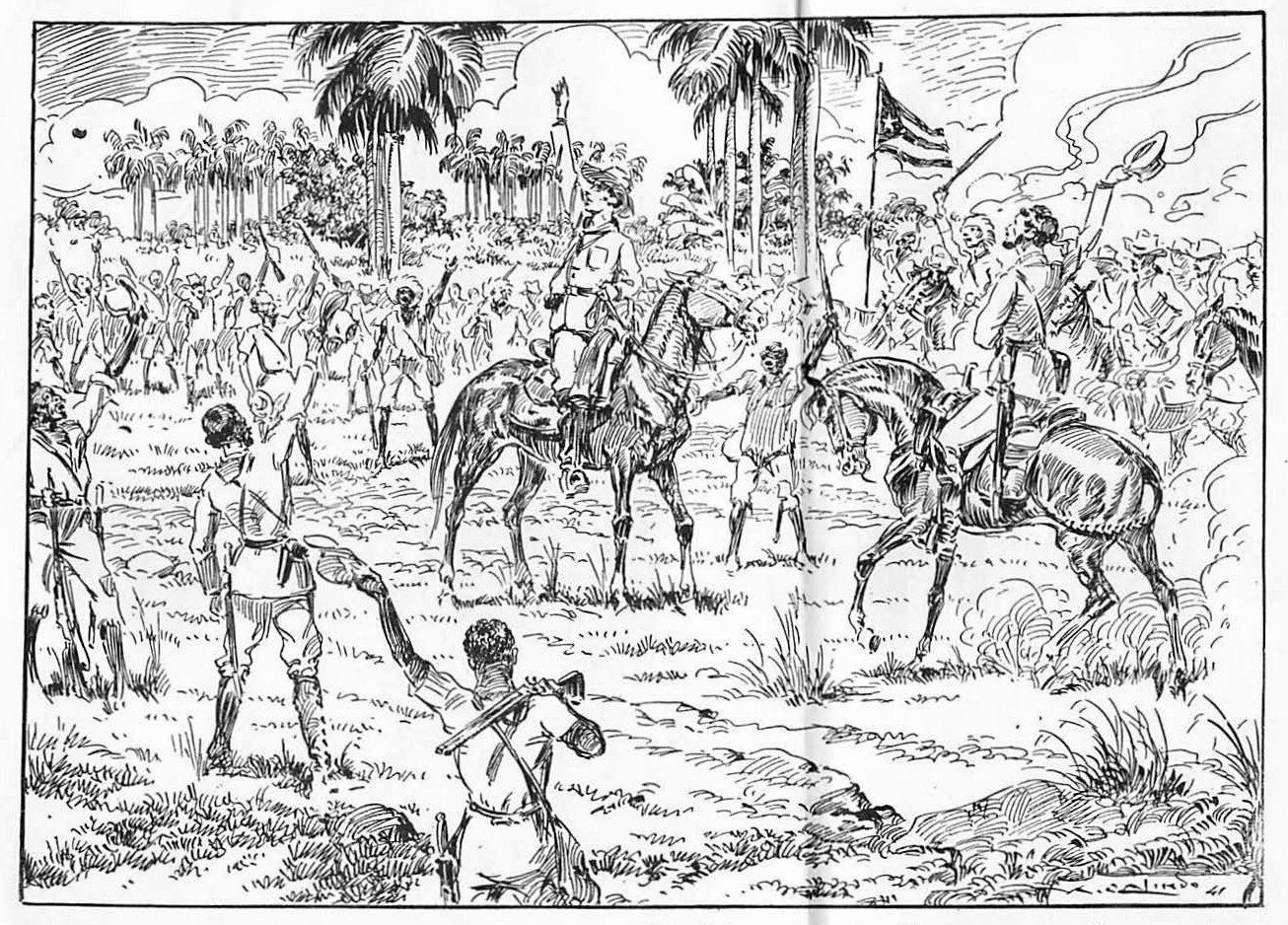

War arrives. Immediately Camagüey’s plains became the scene of glorious encounters for the rebel Cuban fighters. In them Agramonte put his rubric of genius and courage and soon he became more than just a leader, he became an idol to the Camagüeyans in arms. His dashing figure, in the middle of the palm groves, looked to all like a mythological god animated by an internal fire craving heart-felt liberty. Llegó la guerra. Las llanuras camagüeyanas fueron pronto escenario de encuentros gloriosos para las legiones cubanas. En ellos Agramonte puso su rúbrica de genio y valor y pronto fué, más que un jefe, un ídolo para los camagüeyanos en armas. Su figura gallarda, en medio de los palmares, aparecía como si fuera un Dios mitológico animado por el fuego interno de las ansias libertarias más sentidas. |

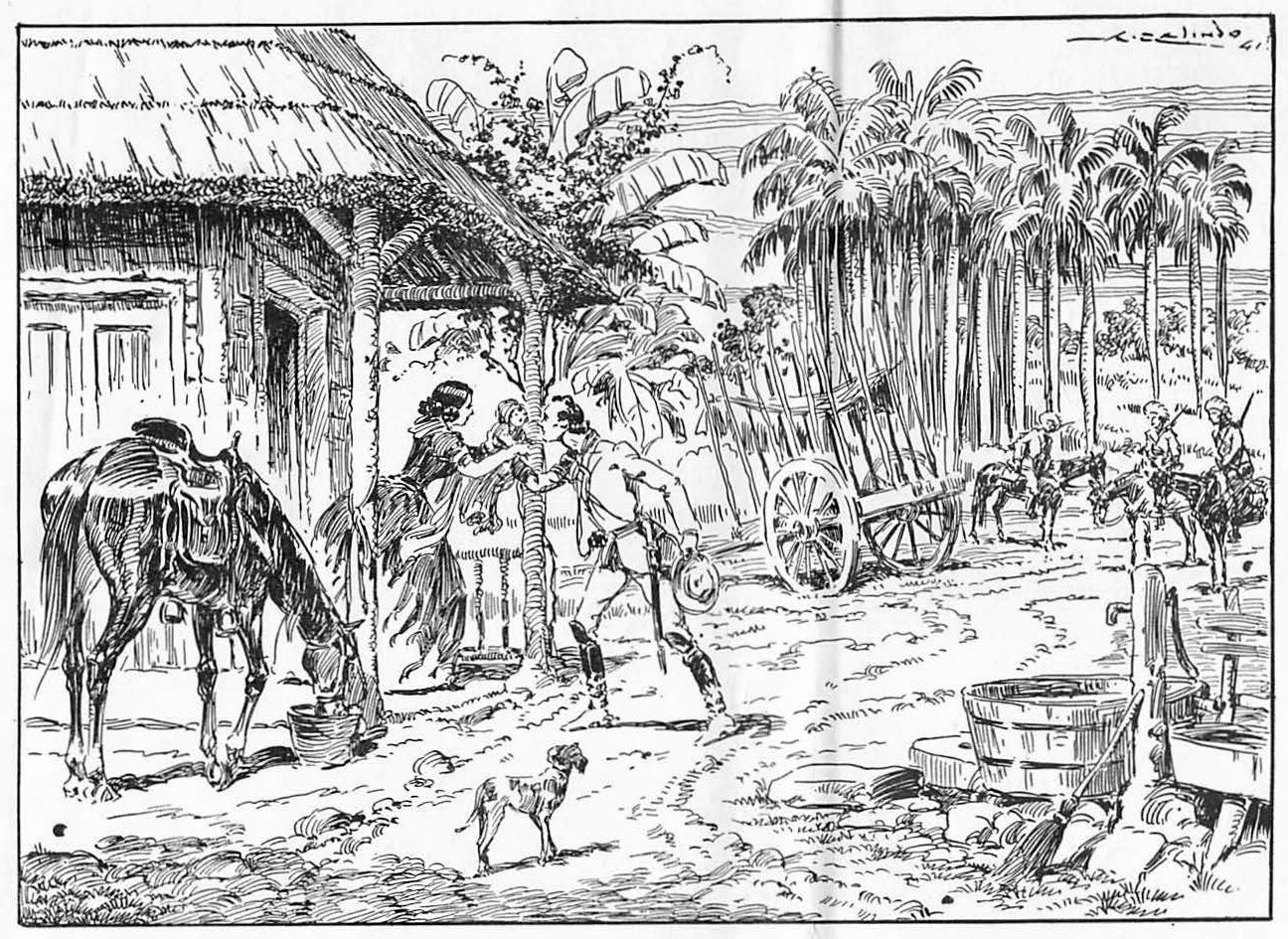

When circumstances permitted, the warrior indulged his heart and visited his adored wife. They were nervous brief encounters. They never knew when and how they were going to end. During the visits, the pair of eternal lovers found themselves in rapture contemplating the tender fruit of their love. Urged by the Cause, el Major—the Major, as he was called by all—always mounted his steed anew, but he was always with Amalia in his exalted soul. Cuando lo permitían las circunstancias, el guerrero complacía a su corazón y visitaba a su esposa adorada. Eran entrevistas nerviosas, breves, que nunca se sabía cuándo y cómo habrían de terminar. En ellas, aquella pareja de eternos enamorados se extasiaba contemplando el tierno fruto de sus amores. Cuando urgido por la Causa, el Mayor tomaba de nuevo su cabalgadura, allí quedaba junto a Amalia toda su alma exaltada. |

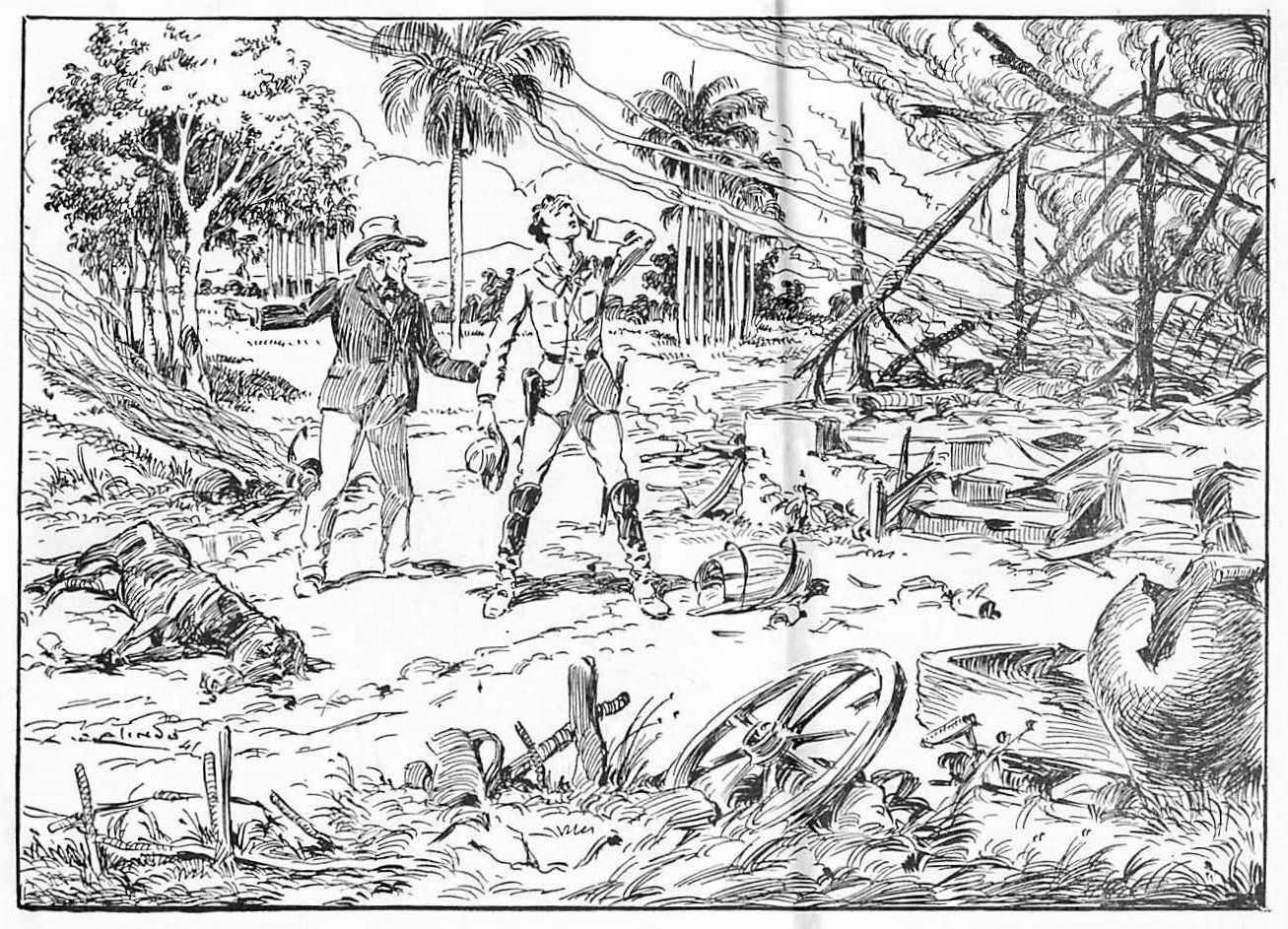

And on May 26, 1870, celebrating the first birthday of his son in the rustic compound deep in the countryside the Major had dubbed “The Idyll,” Agramonte is advised that Spanish troops are approaching. He leaves to investigate, worrying of a betrayal, and returns to the smoking ruins of what had been the nest of his dearest loves. His family has been taken prisoner, and his home destroyed by fire. Y el 26 de mayo de 1870, aniversario del nacimiento de su hijo, fué avisado el Mayor Agramonte, quien se encontraba con su familia en “El Idilio”, que las tropas españolas se acercaban. Y él sale a investigar temiendo una traición. Cuando regresa sólo halla ruinas humeantes en lo que había sido el nido de sus más caros amores. La familia fué hecha prisionera, y la casa destruida por el fuego. Note: Amalia, their son Ernesto and her parents agree “voluntarily” to leave the country and move to New York City, where Ignacio’s second child, a daughter is born. Amalia and Ignacio exchange many letters but Ignacio would never see his family again. |

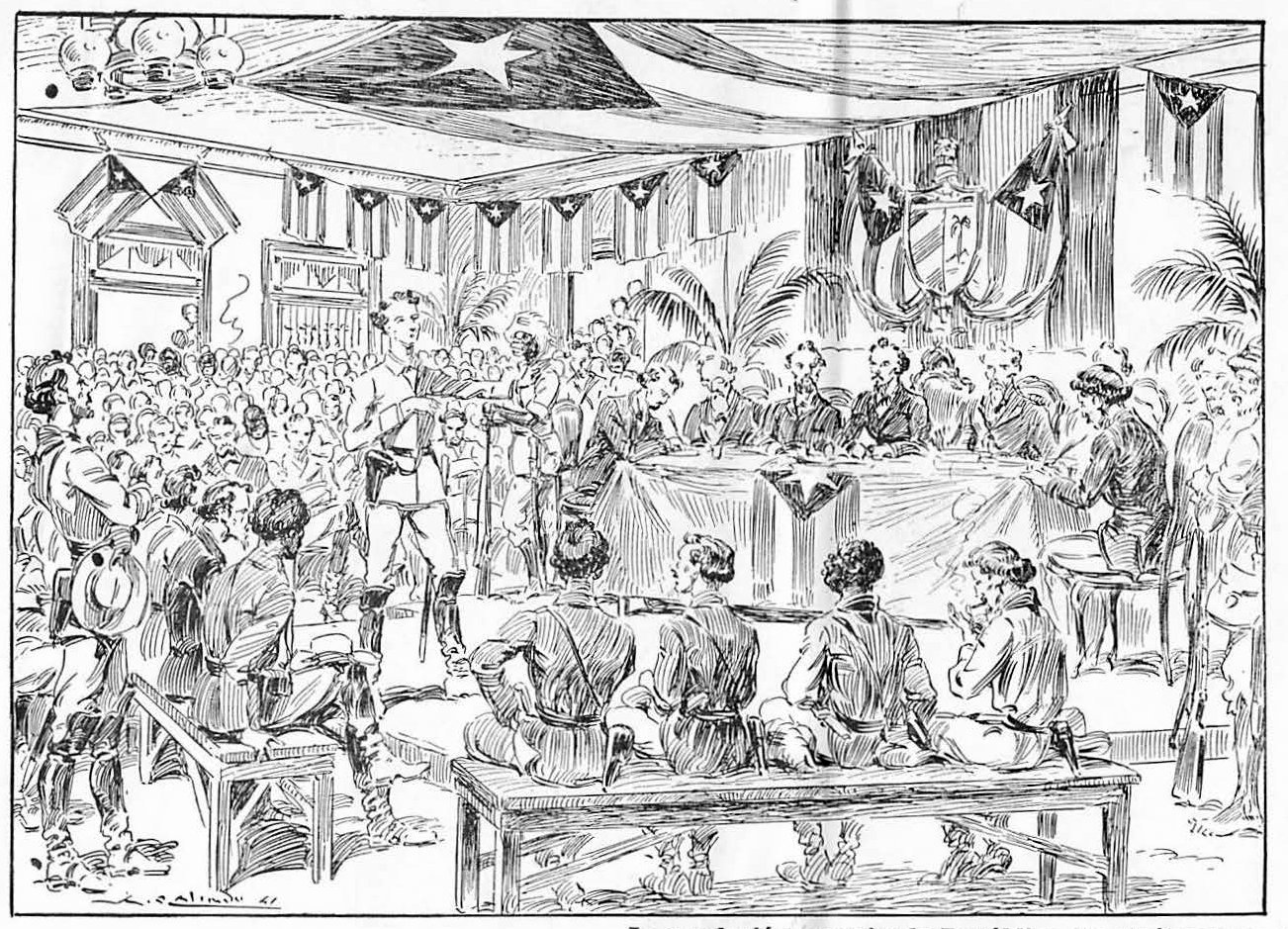

The Revolution organizes the Republic. The Constitutional Assembly meets in Guaimaro, presided by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes with Minister-Delegates Ignacio Agramonte and Antonio Zambrana, charged with drawing up the Constitution. It was a solemn and glorious moment in our history: when Cubans gave proof that their revolutionary movement had a clear and well-defined purpose: Independence as a Republic. La revolución organiza la República. En Guáimaro se reúne la Asamblea Constituyente que preside Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y de la que son Secretarios Ignacio Agramonte Loynaz, y Antonio Zambrana que fueron encargados de redactar la Constitución. Fué un momento solemne y glorioso de nuestra historia en el cual los cubanos dieron prueba de que el movimiento revolucionario tenía un propósito claro y definido. |

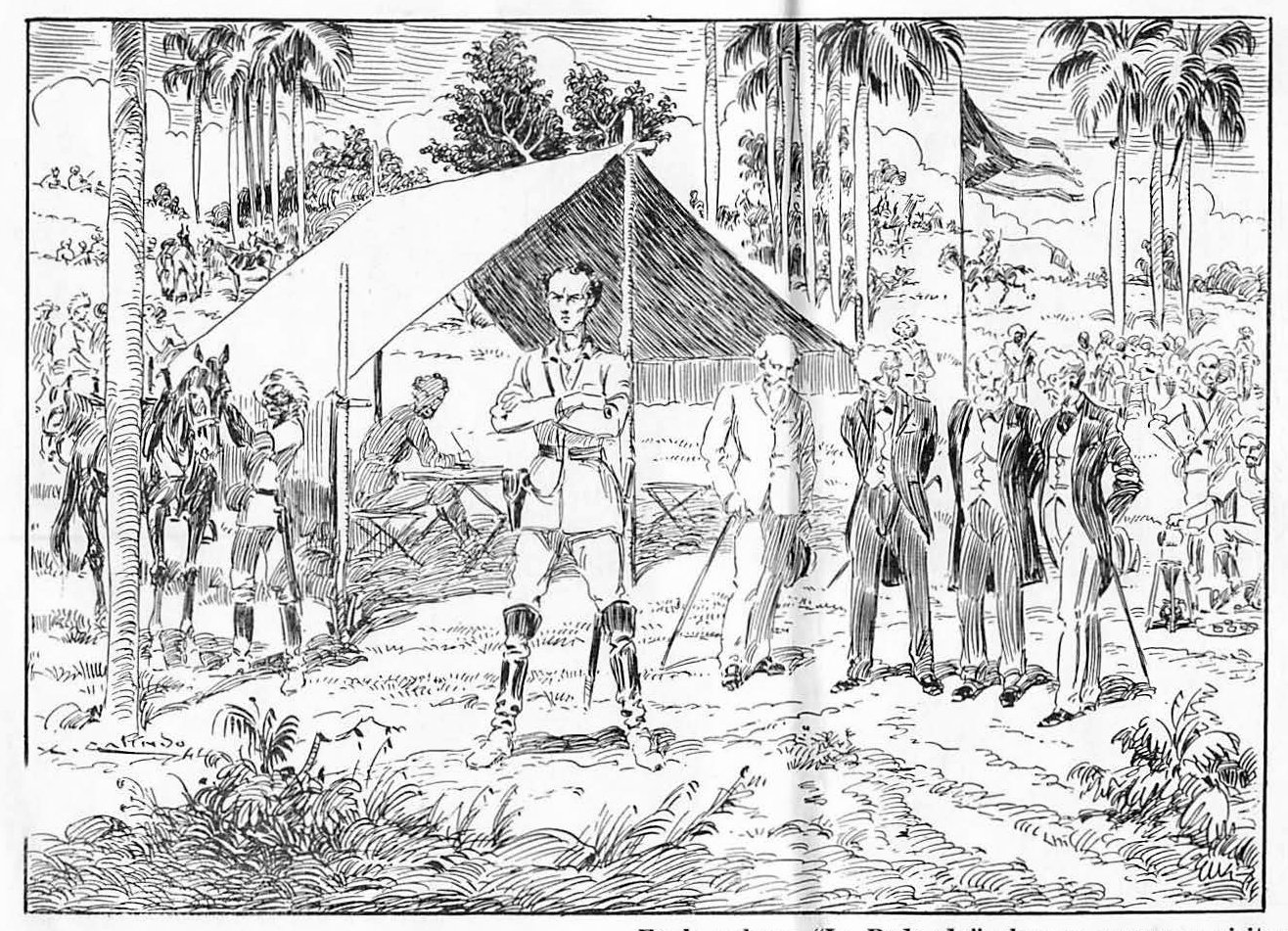

At on the savannah at La Redonda, a delegation visited the Major to convince him of the futility of his efforts. One of them asked, “What basis do you have to continue? With what will you continue this bloody fight?” His dignified response: “With shame ...!” and he turned his back to them. This phrase of his is now famous and was an eloquent summary of the content of his character. En la sabana “La Redonda” algunas personas visitaron al Mayor con el propósito ele tratar de convencerlo de la inutilidad de sus esfuerzos. Uno de ellos le pregunta: "¿Qué elementos tienes para continuar? ¿Con qué vas a seguir esta lucha sangrienta?" "¡Con la vergüenza .. !", replicó con dignidad y volvió la espalda al grupo. Su frase se ha hecho famosa y fué una elocuente síntesis del contenido de su carácter. |

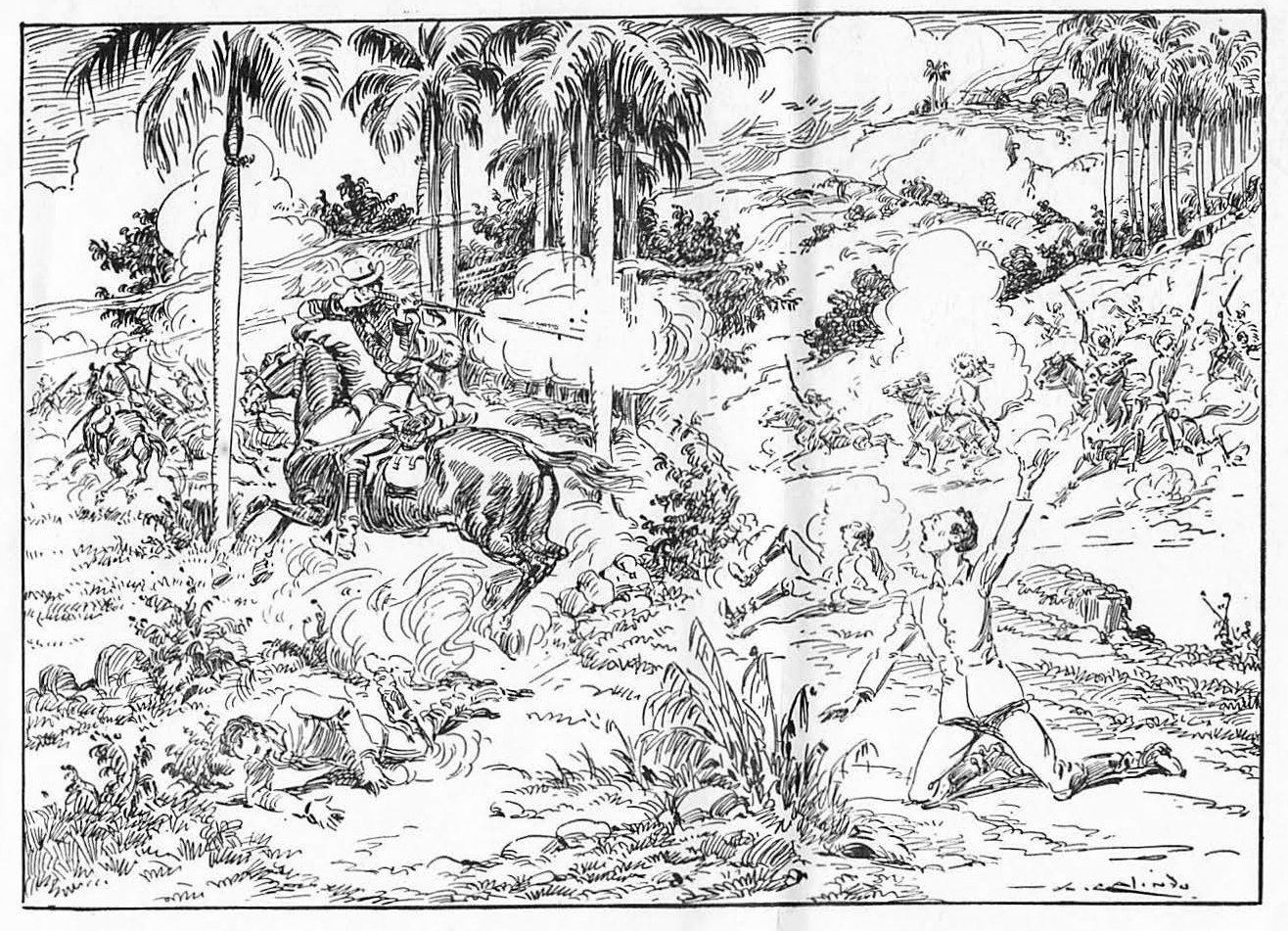

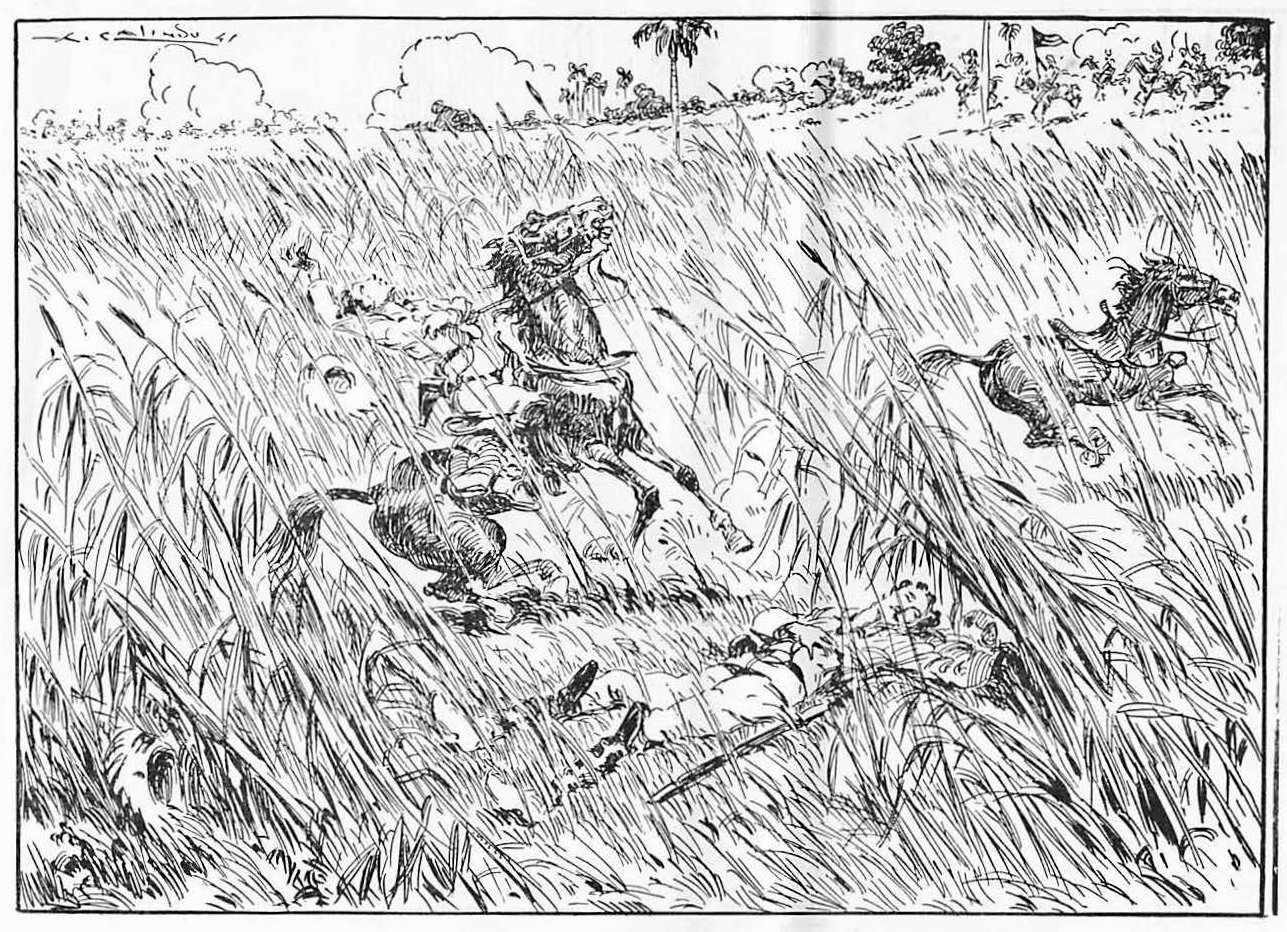

Spanish troops take Julio Sanguily prisoner. When Agramonte is told, he heads out with only 35 horsemen and against overwhelming force, the celebrated charge of the machetes imbues him with an imperishable and unfading halo of glory. Before them cadres of Spanish scatter and Sanguily is rescued. Las tropas españolas cogieron prisionero a Julio Sanguily y cuando Agramonte lo sabe parte contra ellas con sólo 35 jinetes y el ímpetu arrollador de la célebre carga al machete nimbó su frente inmarcesible de gloria imperecedera. Ante ella los cuadros españoles se abrieron y Sanguily fué rescatado. |

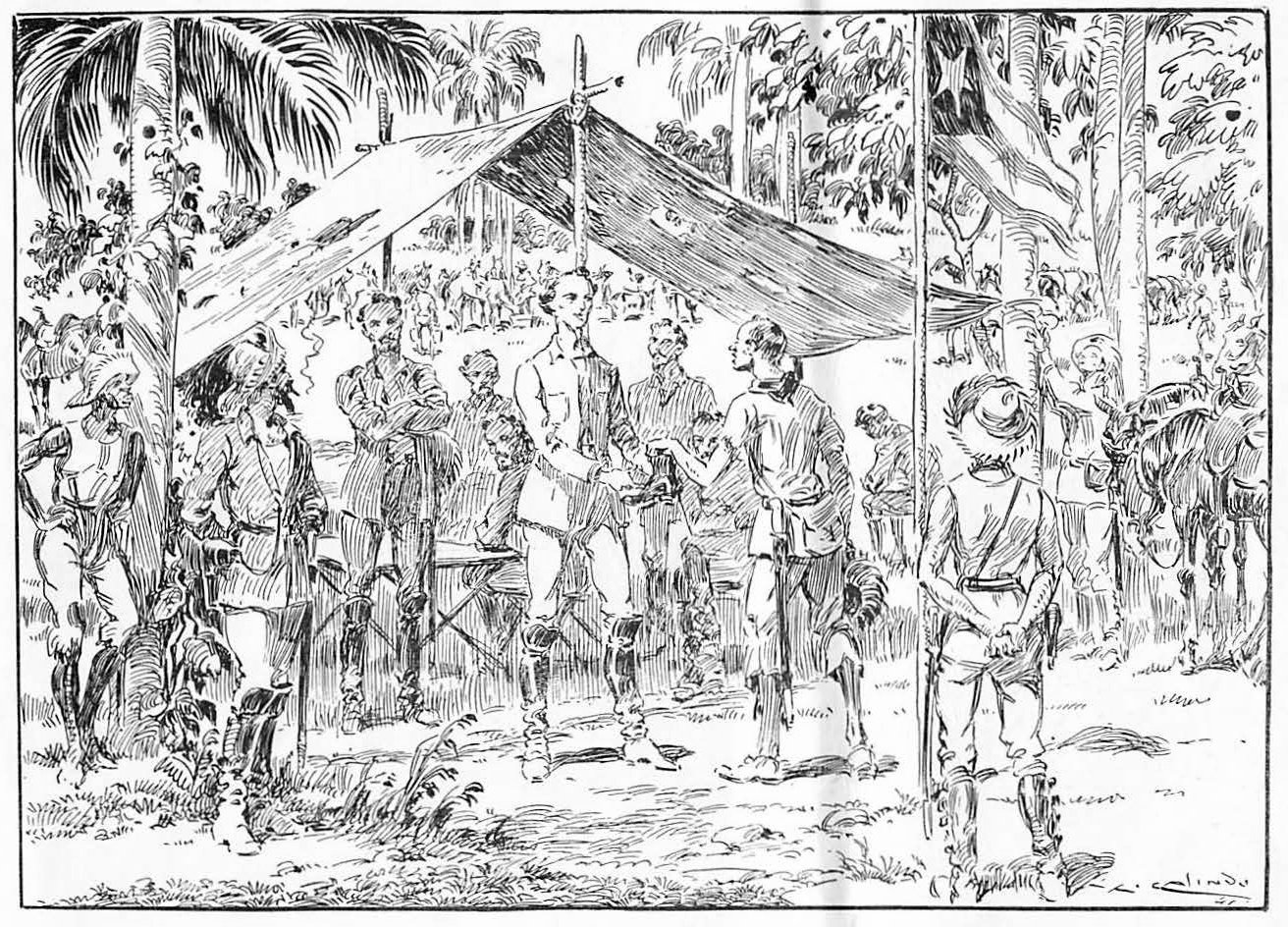

The old manbises from ’68—a nickname for Cuban Revolutionary troops of the Ten Years’ War—tell an anecdote about a shoemaker who tried to ingratiate himself with the Major by making him a gift of a pair of boots made from hutia fur and the leather seat from a camp chair. Agramonte, always selfless and a peerless comrade, without accepting them told the shoemaker, “return with a pair for each of my soldiers together with this pair for me, and I will use them with pleasure.” Quick to sacrifice, Agramonte shared everything with his troops. Y dicen los viejos mambises del 68 que, en oportunidad en que un zapatero mambí quiso obsequiar al Mayor con un par de botas que hiciera con la piel de una jutía y el cuero de un taburete, Agramonte, todo abnegación y compañero sin par, sin aceptarlas le dijo: "Traed un par a cada uno de mis soldados, con éstas para mí, y entonces gustoso las usaré". Ignacio Agramonte, presto al sacrificio, todo lo compartió con sus tropas. |

The fateful day arrived: May 11, 1873. Ignacio Agramonte falls mortally wounded in a paddock at Jimaguayú. The height of the grass prevents the Cubans from first noticing the misfortune. But it is certain: their idol has fallen, and his generous blood had soaked the heroic soil, impregnating Camagüey’s fertile soil so the leafy and robust tree of the Republic could one day bear the fruits of liberty. That day was a painful day for the Revolution. Llegó el día aciago: el 11 de Mayo de 1873, Ignacio Agramonte cae mortalmente herido en el potrero de Jimaguayú. La altura de la yerba impide a los cubanos darse cuenta de la desgracia; pero ella era cierta: había caído el ídolo y su sangre generosa regaba la manigua heróica y fecundaba la fértil tierra Camagüeyana para que en ella fructificara el árbol frondoso y robusto de la República. Fué aquel un día doloroso para la revolución. |

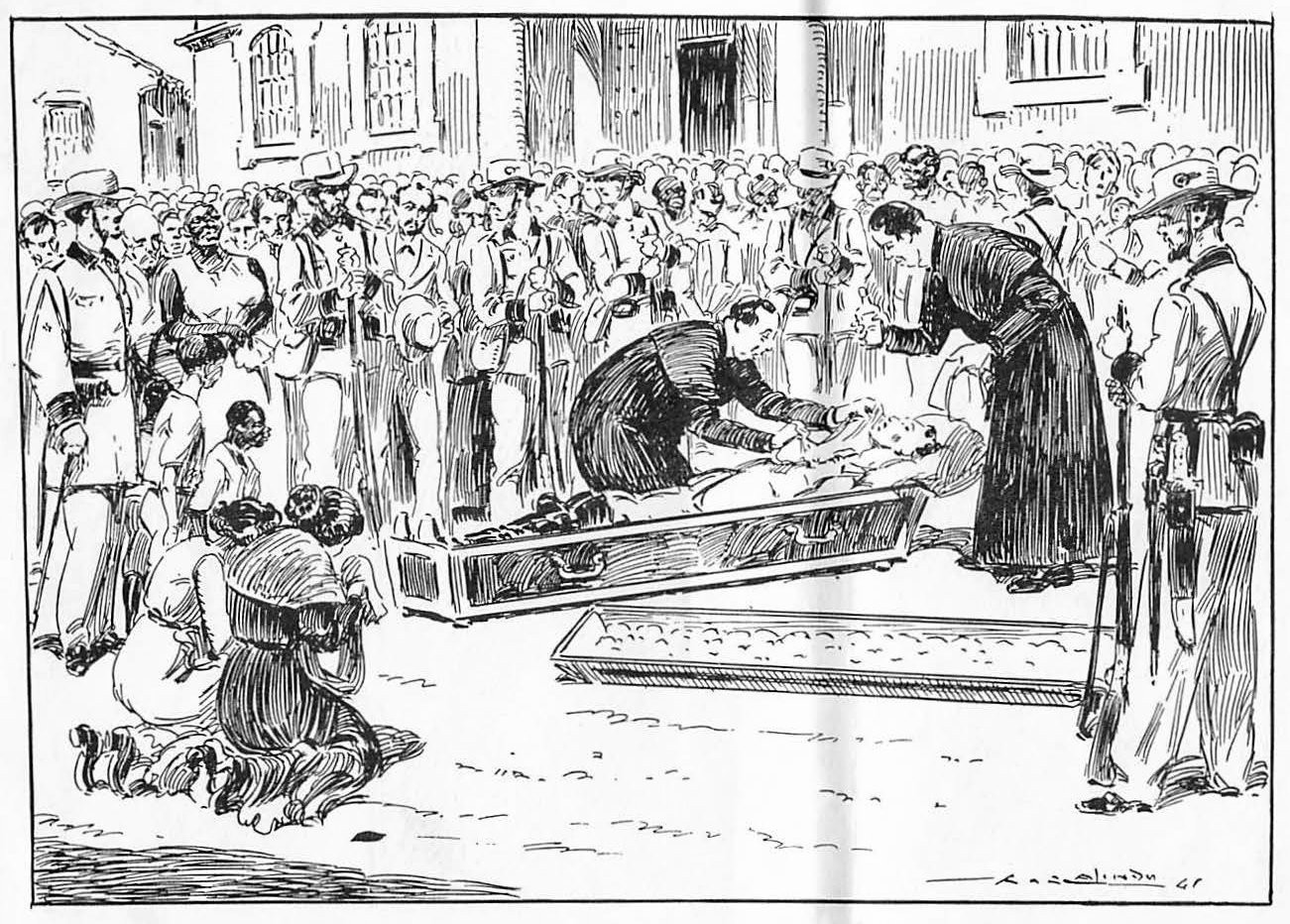

Agramonte’s body is conveyed to Camagüey, and at their hospital the pious Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God lay him out and clean his virile face. Cuban women cry and pray. The hearts of patriots are heavy with anguish while the Spanish Army and sympathizers of the colonial regimen celebrate their triumph. They ignore the fact, as Máximo Gómez later said, that Agramonte would inflict more hurt on Spain dead than he had caused when he lived. Traído el cadáver de Agramonte a Camagüey es tendido en el Hospital de San Juan de Dios, donde dos piadosos sacerdotes limpian su rostro viril. Las cubanas lloran y rezan. El corazón de los patriotas se comprime con la angustia, y el ejército español y los simpatizantes con el régimen colonial celebran su triunfo, ignorando que, como dijera Máximo Gómez, Agramonte iba a hacerle más daño a España, muerto, que el que le había hecho en vida. Note: Spanish authorities were in control of the city. They order his body paraded through town, summarily burned, and the ashes dispersed. |

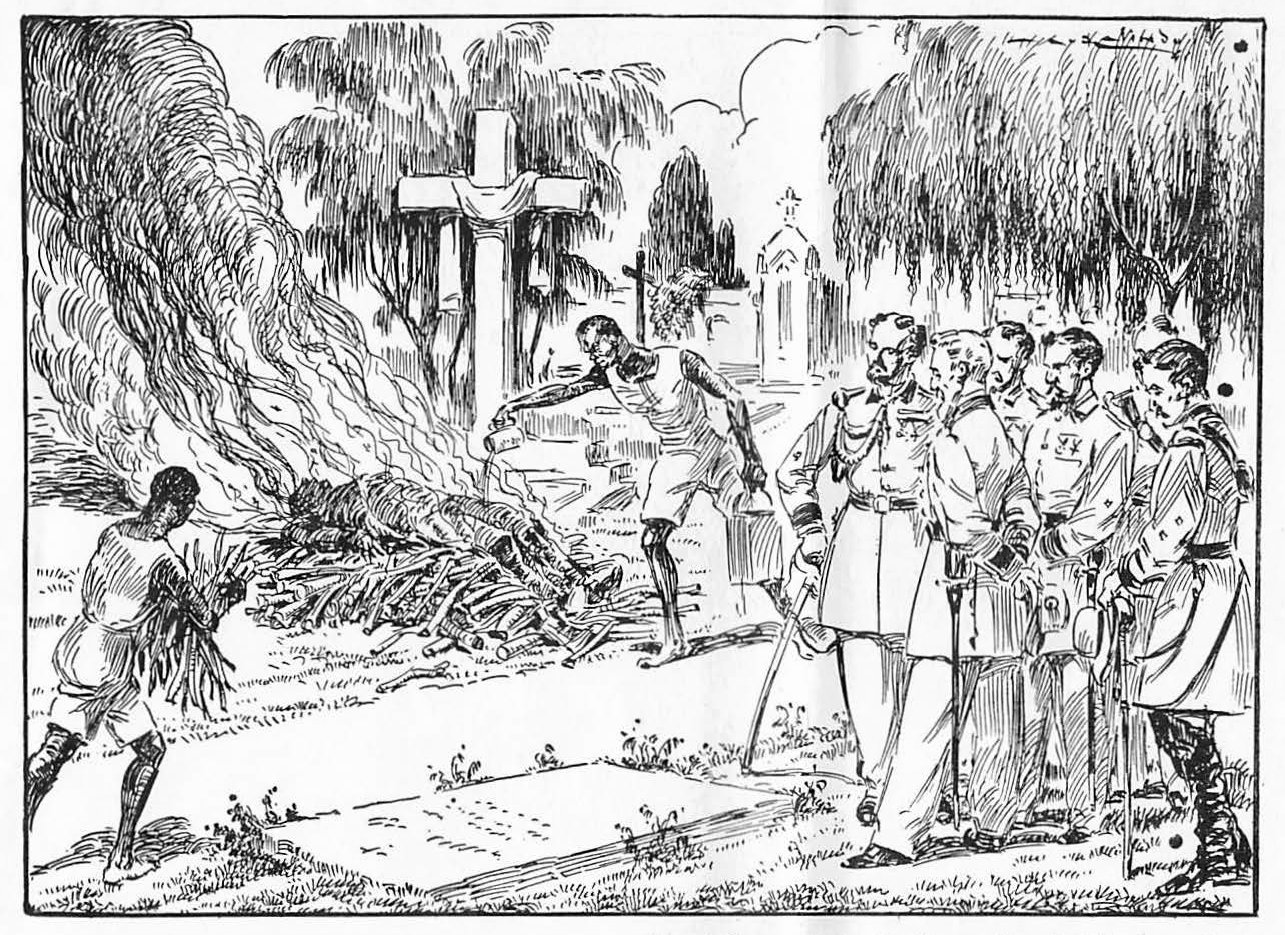

His body is cremated at Camagüey’s cemetery. That glorious body is consumed and those flames that touched his flesh created smoke that rose to the heavens—to the hero. Of his body only ashes remained, so instead each Cuban heart erects an altar to his memory. And on the Republic’s own soul there appears his name, inscribed in gold letters. Agramonte died and was cremated. From that moment he becomes immortal to the Cuban people. En el Cementerio de Camagüey fué incinerado su cadáver. El cuerpo glorioso se consumió y aquellas llamas que lamían sus carnes, hechas humo elevaron a las alturas al héroe. De su cuerpo sólo quedaron cenizas; pero, en cambio, en cada corazón cubano se elevó un altar a su memoria y en el alma de la República misma aparece su nombre grabado con letras de oro. Agramonte murió y fué quemado. En el pueblo cubano, fué inmortal desde entonces. Note: The war will continue for five more years. |

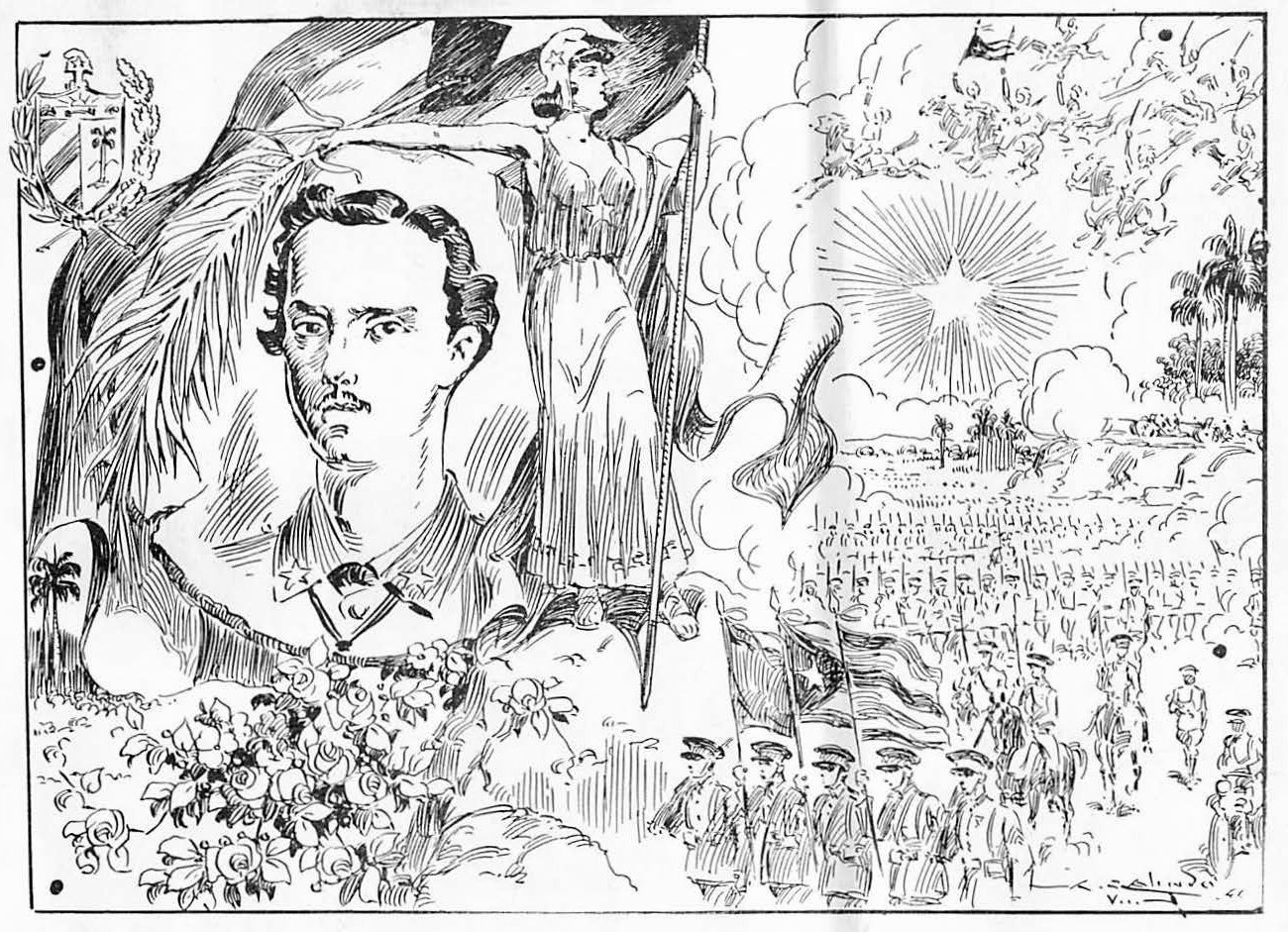

It is now one hundred years after his birth. In our history, the Glorious Liberating Army, at the magic incantation of his name, tightened its ranks and spiritedly charged, pushing against the bulwark until tyranny surrendered. In each person’s breast Republican Cuba raised an altar, and on that altar initiated a cycle where our native land shines resplendent like the light of a great star. That great star is the generous heart of our immortal Bayard!—Our fearless knight beyond reproach. Y transcurrieron cien años de su Natalicio. En nuestra Historia, el Glorioso Ejército Libertador al mágico conjuro de su nombre, apretó sus filas y cargó briosamente y a su empuje se rindió el baluarte de la tiranía. Cuba Republicana levantó en cada pecho un altar y sobre el ciclo de la patria brilló con refulgente luz una estrella: ¡el corazón generoso de nuestro inmortal Bayardo! |

|

The Ten Years’ War ends in 1878 with amnesty and pardons, with Spain promising to treat its colony better and seating Cuban representatives in the Spanish House of Deputies in Madrid. But after sixteen years of relative quiet and prosperity, the Spanish are again suppressing freedoms, imposing onerous taxes and the crown-appointed Governors are becoming more and more despotic. In 1891 José Martí calls for revolt and insurgency begins anew. By 1898, the Cuban freedom fighters see the possibility of sucess and independence, but at that point the United States intervenes, declaring war on Spain. The Spanish American War is won and Spain relinquishes control of Cuba. Cuba is finally free, but with an asterisk. (* the United States forces itself into the Cuban Constitution). Many Cubans felt at the time that their inevitable victory was taken from them when the United States joined the fight. Amalia Simoni would never remarry. She moved back to Camagüey in 1892 with their daughter Herminia and grandchildren and later moved to Havana, where she died in 1918, 45 years after Ignacio’s death. At her funeral her nephew, the physician Dr. Aristides Agramonte, thanked the crowd for “accompanying to this sacred place the mortal remains of the exemplary companion of the bravest, most courageous and daring soldier of our liberties, the undiminished hero of Jimaguayú, Major General Ignacio Agramonte.” |

|

Ignacio Agramonte (1841–1873) — our hero.

Joaquín de Agüero (1816–1851) — He freed his slaves in 1843 and handed them each a plot of land to make a living—alarming the Spanish authorities—and he self-exiled to the United States to avoid reprisal. He later returned to his farm near Guáimaro, actively participating in clandestine independence movements. After one of them, he and three compatriots were captured and he was summarily executed by firing squad by Spanish troops along with his three compatriots, Miguel Benavides, Tomás Betancourt , and Fernando de Zayas.

Antonio Zambrana (1846–1822) — A minister-delegate to the Guáimaro Constitutional Assembly like Ignacio Agramonte, the two draft the Constitution of 1869 with input from the Assembly. Manuel de Quesada (1830–1886) — Mexican who leaves Mexico for Cuba in 1867. Fights alongside Cubans during the Ten Years’ War. Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (1819–1874)— a Cuban planter who freed his slaves and made the declaration of Cuban independence in 1868 which started the Ten Years’ War at Demajagua. Julio Sanguili — Brigadier General during the Ten Years’ War. Wounds had hobbled him and he asked and received permission from Agramonte to take a few days at a nearby ranch. A Spanish column discovered him there and captured him. They were returning to Camagüey double-time with other columns when Ignacio Agramonte rescued him. Los Mambises — The term mambises (singular: mambí) refers to the Cuban independence soldiers who fought against Spain in the Ten Years’ War (1868–78) and Cuban War of Independence (1895–98). The term has been applied to persons who fought for independence during any of the Cuban wars of independence. The word mambí is associated with Juan Ethnnius Mamby also known as Eutimio Mambí. Mamby was a black Spanish military officer who deserted to fight with the Dominicans against the Spanish in Santo Domingo in 1846. As Mamby and his men gained fame, the Spanish soldiers began referring to them as “the men of Mamby” or “mambises”. Spanish soldiers in Cuba began calling the independence fighters mambises, noting the similar tactics and use of machetes by Cuban fighters. Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God — A Roman Catholic order founded in 1572 by Juan de Dios, a Spaniard of Portuguese decent. They built hospitals and that serve the sick and afflicted throughout the world. Today they operate health initiatives and run clinics and hospices for the poor worldwide, but no longer in Cuba. The Bayard, El Bayardo — refers to Pierre Terrail, chevalier de Bayard. The Knight of Bayard lived in the 16th century in France and is known as “the knight without fear and beyond reproach” and “the good knight.” |

|

The last pages of the publication included this appeal for the erection of a museum to Camagüey’s history to be named the Ignacio Agramonte Museum of Camagüey. The Shame bequeathed to us by Agramonte imposes duties

|

These prestigious institutions in Camaguey back this Appeal:THE TERRITORIAL COUNCIL OF INDEPENDENCE VETERANS OF CAMAGUEY: THE DELEGATION OF INDEPENDENCE VETERANS OF CAMAGUEY: THE ASSOCIATION OF SONS AND GRANDSONS OF INDEPENDENCE VETERANS OF CAMAGUEY: THE LYCEUM SOCIETY OF CAMAGUEY: THE CAMAGUEY TENNIS CLUB SOCIETY: THE ROTARY CLUB OF CAMAGUEY: Enrique Fariñas, President THE COLLEGE OF PROVINCIAL ARCHITECTS: THE SANTA MARIA COUNCIL 2479, KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS: THE PHARMACEUTICAL COLLEGE OF CAMAGUEY: THE CIRCLE OF PROFESSIONALS OF CAMAGUEY: THE COLLEGE OF LAWYERS OF CAMAGUEY CATHOLIC KNIGHTS OF CUBA, UNION 62: CATHOLIC KNIGHTS OF CUBA, Union 77: RAILWAY WORKERS ATHLETIC CLUB OF CAMAGUEY: THE RAILWAY WORKERS ACTION ASSOCIATION OF CAMAGUEY: THE BROTHERHOOD OF RAILWAY WORKERS OF CUBA, CENTRAL OFFICE: Prestigiosas Instituciones de Camagüey que respaldan esta ApelaciónPOR EL CONSEJO TERRITORIAL DE VETERANOS

DE LA INDEPENDENCIA DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA DELEGACION DE VETERANOS DE LA INDEPENDENCIA DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA ASOCIACION DE IDJOS Y NIETOS DE VETERANOS DE LA INDEPENDENCIA DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA SOCIEDAD “EL LICEO” DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA SOCIEDAD “CAMAGUEY TENNIS CLUB”: POR EL “CLUB ROTARIO” DE CAMAGUEY: POR EL COLEGIO PROVINCIAL DE ARQUITECTOS DE CAMAGUEY: POR EL CONSEJO SANTA MARIA 2479 DE LOS CABALLEROS DE COLON: POR EL COLEGIO FARMACEUTICO DE CAMAGUEY: POR EL CIRCULO DE PROFESIONALES DE CAMAGUEY: POR EL COLEGIO DE ABOGADOS DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA UNION 62 DE LOS CABALLEROS CATOLICOS DE CUBA: POR LA UNION 77 DE LOS CABALLEROS CATOLICOS DE CUBA: POR EL CLUB ATLETICO FERROVIARIO DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA ASOCIACION ACCION FERROVIARIA DE CAMAGUEY: POR LA HERMANDAD FERROVIARIA DE CUBA, DIRECCION CENTRAL: |

|

The idea of a museum became a reality. It can be found The General Ignacio Agramonte Provincial Museum today in an imposing building on the Avenue of the Martyrs in Camagüey. El concepto del museo se convirtió en realidad. El Museo Provincial General Ignacio Agramonte se encuentra hoy en un majestuoso edificio in la Avenida de los Martires en Camagüey. |